When you see a commercial for a new prescription drug, it’s hard not to feel like you’ve found the answer to your health problem. The scenery is peaceful - people hiking, laughing at the beach, playing with grandchildren. The voiceover says it’s safe, effective, and approved. But what you don’t hear is that there’s a cheaper version, just as effective, sitting on the pharmacy shelf. This isn’t an accident. It’s marketing.

The Power of Branding Over Biology

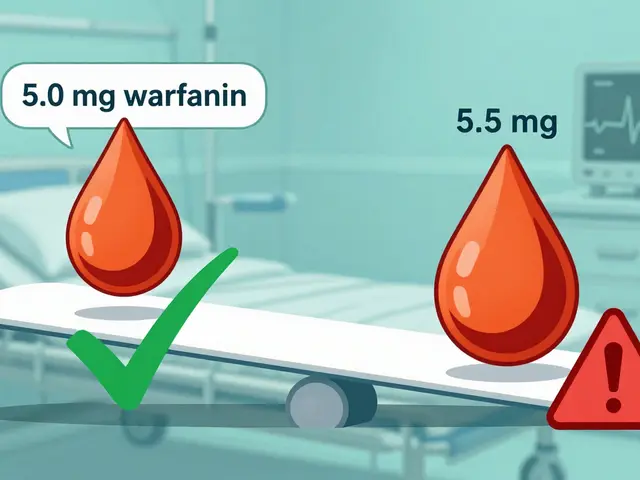

In the U.S., pharmaceutical companies spend over $6 billion a year on direct-to-consumer (DTC) advertising. That’s more than ten times what they spent in 1996. And it works. Research from the Wharton School shows that for every 10% increase in ad exposure, prescriptions for those drugs go up by about 5%. But here’s the twist: most of those prescriptions aren’t for the branded drug shown in the ad. They’re for the generic version in the same drug class. Why? Because patients walk into the doctor’s office and ask for the drug they saw on TV. The doctor, knowing the brand is expensive and the generic is just as good, writes the prescription for the cheaper option. The ad didn’t sell the brand - it sold the drug class. That’s the spillover effect. Advertising for Lipitor, for example, boosted prescriptions for all cholesterol-lowering meds, including generics like simvastatin. But here’s the catch: even though generics get more prescriptions because of these ads, patients still believe the branded version is better. A national survey found that doctors often give in to patient requests for advertised drugs - even when they think it’s unnecessary. In one study, physicians filled 69% of requests for treatments they deemed inappropriate. That’s not just influence. That’s manipulation.What the Ads Don’t Tell You

Pharmaceutical ads are carefully designed. They show happy people doing things you want to do. They mention side effects - briefly - buried under upbeat music and smiling faces. The FDA found that even after seeing an ad four times, people still barely remembered the risks. Benefit information stuck a little better, but not enough. Meanwhile, generic drugs? They don’t run ads. Ever. So when you hear about a new branded medication for diabetes or depression, you assume it’s the best option. You don’t know that the generic version has the exact same active ingredient, same FDA approval, same effectiveness - but costs 80% less. The ad doesn’t mention it. The doctor rarely brings it up unless you ask. A study analyzing 230 pharmaceutical ads found that scenes with nature, families, and outdoor activities lasted longer than scenes explaining side effects. The emotional hook is stronger than the medical facts. That’s not a flaw - it’s the strategy. Your brain remembers how you felt watching the ad, not what the fine print said.The Cost of Being Influenced

You might think more prescriptions mean better health. But research shows that’s not always true. Patients who start a new medication because of an ad are actually less likely to stick with it long-term. Their adherence is lower than those who started because their doctor recommended it. Why? Because they weren’t seeking treatment - they were responding to a commercial. This isn’t just about money. It’s about health outcomes. When people start a drug they don’t really need, or don’t take consistently, it leads to wasted resources and potential harm. A 10% increase in advertising led to only a 1%-2% improvement in adherence among existing users. That’s a tiny gain for a massive cost. In 2020, every dollar spent on DTC advertising generated over $4 in sales. That’s a huge return. But who pays the rest? You do - through higher insurance premiums, out-of-pocket costs, and a healthcare system that overuses expensive drugs because patients think they’re better.

Why Generics Are the Silent Winners (and Losers)

Generics are the unsung heroes of modern medicine. They’re rigorously tested. They’re identical in active ingredients. They’re approved by the same agency that approves the branded versions. And yet, because they don’t advertise, they’re seen as second-rate. This perception gap isn’t based on science. It’s based on exposure. You see a commercial for a branded drug every day. You never see one for the generic. So your brain fills in the blanks: if it’s advertised, it must be better. That’s classic marketing psychology - availability bias. The thing you see most often feels more real, more important, more effective. Doctors aren’t immune either. Studies show that when patients ask for a specific drug, doctors are far more likely to prescribe it - even if they’d normally choose a generic. It’s not that they’re weak. It’s that the system is designed to make patients feel entitled to the advertised option.Is There a Better Way?

Some experts argue DTC ads do have value - they raise awareness about under-treated conditions. Someone who never knew they could get help for depression might see an ad and finally talk to their doctor. That’s real. But the current system is unbalanced. Ads focus on branded drugs, not treatment options. They don’t mention generics. They don’t compare costs. They don’t encourage lifestyle changes. And they don’t give you enough information to make an informed choice. What if ads were required to show the generic alternative? What if they had to state the price difference? What if they showed the same number of side effects as benefits? Those changes wouldn’t stop awareness - they’d make it honest. The FDA allows DTC ads because they believe patients should be informed. But if the information is skewed, misleading, or incomplete, are patients really informed? Or are they just persuaded?

What You Can Do

If you’re prescribed a new medication, ask three questions:- Is there a generic version available?

- Is it just as effective?

- How much will it cost?

Ashley Paashuis

February 20, 2026 at 21:57It's fascinating how marketing can manipulate perception so thoroughly. I never realized that generic drugs are bioequivalent-same active ingredients, same FDA standards. The fact that people believe branded drugs work better just because they saw an ad is a textbook case of availability bias. It makes me wonder how many other areas of life we’re misled by repeated exposure to polished narratives.

Oana Iordachescu

February 21, 2026 at 17:39They’re not just advertising drugs-they’re advertising *fear*. The entire system is engineered to make you feel broken unless you buy their solution. And the FDA? Complicit. They allow ads that bury side effects under smiling grandparents, while generics-proven, safe, cheaper-are silenced. This isn’t capitalism. This is psychological warfare disguised as healthcare.

Davis teo

February 23, 2026 at 08:04OMG I JUST REALIZED-I’ve been paying extra for branded meds for YEARS because I thought they were ‘stronger.’ Like, I had no idea the generic was literally the same pill. My doctor never mentioned it. My insurance didn’t flag it. And now I’m sitting here wondering how many other things I’ve been scammed on. I feel so manipulated. Like, seriously-how do we fix this??

Michaela Jorstad

February 23, 2026 at 19:44It’s heartbreaking, really. People aren’t dumb-they’re just bombarded with messaging that plays on emotion, not logic. And when you’re sick, scared, or in pain, you don’t want to parse fine print. You want hope. But hope shouldn’t cost $300 when $60 does the exact same thing. We need transparency. Not just in ads, but in prescribing practices too.

Chris Beeley

February 24, 2026 at 02:17Let us not pretend this is merely about pharmaceuticals-it is a microcosm of late-stage capitalist alienation. The commodification of health, the reduction of biological necessity into consumer preference, the manufactured scarcity of perceived efficacy-all orchestrated by corporate interests that have co-opted medical authority. The generic drug, stripped of branding, becomes an ontological non-entity in the public imagination. A silent hero, yes, but one rendered invisible by the spectacle of spectacle itself. We are not patients; we are data points in a profit algorithm.

Arshdeep Singh

February 24, 2026 at 23:20Bro, you think this is bad? Wait till you find out how they market mental health meds. People are getting prescribed SSRIs because they saw a 15-second ad while scrolling TikTok. Meanwhile, therapy? No ad. No sponsor. No cute dog running on a beach. So guess what? Everyone’s on pills. No one’s talking. We’re not healing-we’re just numbing and paying for it.

James Roberts

February 25, 2026 at 13:42Oh wow, so the real villain isn’t Big Pharma-it’s our own brains? We’re the ones who let the ad convince us the branded version is better? That’s almost poetic. And yet… we still have to ask for the generic. The system doesn’t just *allow* manipulation-it *requires* us to fight it ourselves. Like, congratulations, we’re now medical detectives. And we’re supposed to be grateful?

Danielle Gerrish

February 26, 2026 at 22:18I had a friend who was on Lipitor for years-$200/month-until I told her about simvastatin. She switched, saved $150/month, and her cholesterol dropped even more. But here’s the kicker: she cried when she found out she’d been paying extra for nothing. She said, ‘I felt like I was being lied to every time I saw that commercial.’ And she was right. That commercial didn’t just sell a drug-it sold a lie. And now I’m mad for her. And for everyone else.

Liam Crean

February 27, 2026 at 09:00I’ve been a pharmacist for 12 years. Patients ask for the branded drug every single day. Most don’t even know what ‘generic’ means. I explain it. They nod. Then they leave with the expensive one anyway. It’s not about knowledge. It’s about perception. And perception is built by ads. The system isn’t broken-it’s working exactly as designed.

madison winter

February 27, 2026 at 16:14So… what’s the point? We all know ads are manipulative. We all know generics are cheaper. We all know doctors get pressured. Nothing changes. So why are we even talking about this?

Davis teo

February 28, 2026 at 09:20Wait-so if I ask for the generic, does that mean my doctor thinks I’m cheap? Or worse… that I don’t care about my health? I’m terrified to ask now. What if they judge me? What if they think I’m too poor to afford the ‘real’ medicine? This whole thing is emotionally exhausting.

Jeremy Williams

March 2, 2026 at 06:42As someone raised in a culture where healthcare is a communal responsibility-not a market transaction-I find this deeply alien. In Nigeria, where I grew up, you take what works. No ads. No branding. Just efficacy. Here, the medicine is secondary to the narrative. We’ve turned healing into a branding contest. And the losers? The people who can’t afford the marketing.