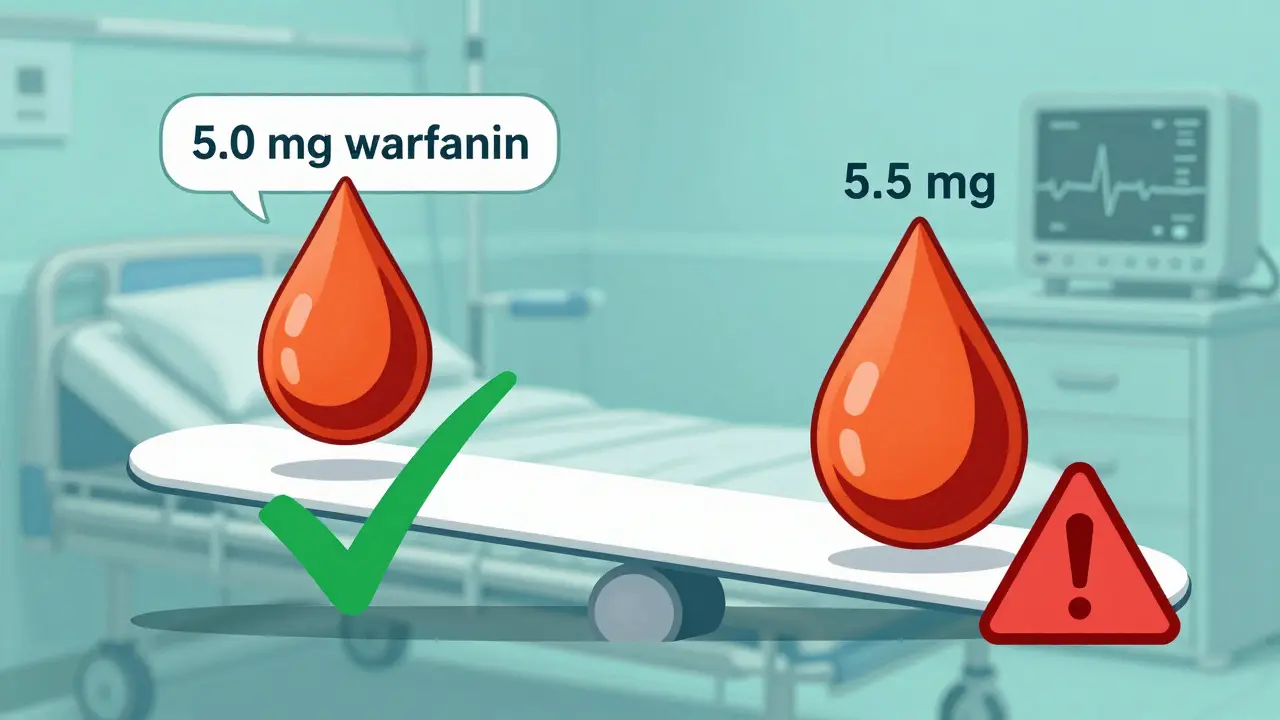

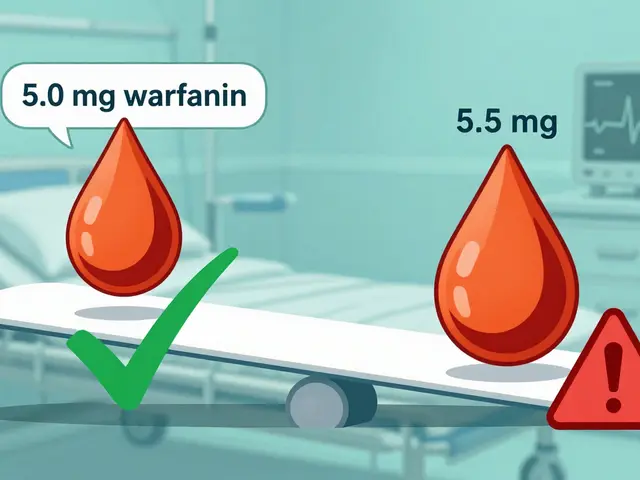

When a doctor prescribes a medication like warfarin, digoxin, or phenytoin, the difference between a safe dose and a dangerous one can be razor-thin. These are NTI drugs - Narrow Therapeutic Index drugs - where even a 10% change in blood levels can lead to treatment failure or life-threatening side effects. That’s why the FDA doesn’t treat them like regular generic drugs. The rules for proving they work the same as the brand-name version are far stricter, and getting it wrong can have serious consequences.

What Makes a Drug an NTI Drug?

The FDA defines an NTI drug as one where the gap between the minimum effective dose and the minimum toxic dose is very small. In 2022, the agency settled on a clear, data-driven cutoff: if a drug’s therapeutic index is 3 or less, it’s classified as NTI. That means the toxic dose is no more than three times the effective dose. Out of 13 drugs studied, 10 fit this definition. The rest hovered between 3 and 5 - too close for comfort, but not quite crossing the line.

It’s not just about numbers. The FDA also looks at whether the drug requires regular blood monitoring, if doses are adjusted in small increments (like 5-10% changes), and how much the drug levels vary from one person to another. Drugs like tacrolimus, lithium, and carbamazepine are textbook NTI cases. Take warfarin: a patient on 5 mg per day might bleed badly if they get 5.5 mg. That’s not a typo - half a milligram can mean the difference between clot prevention and internal bleeding.

Why Standard Bioequivalence Rules Don’t Work for NTI Drugs

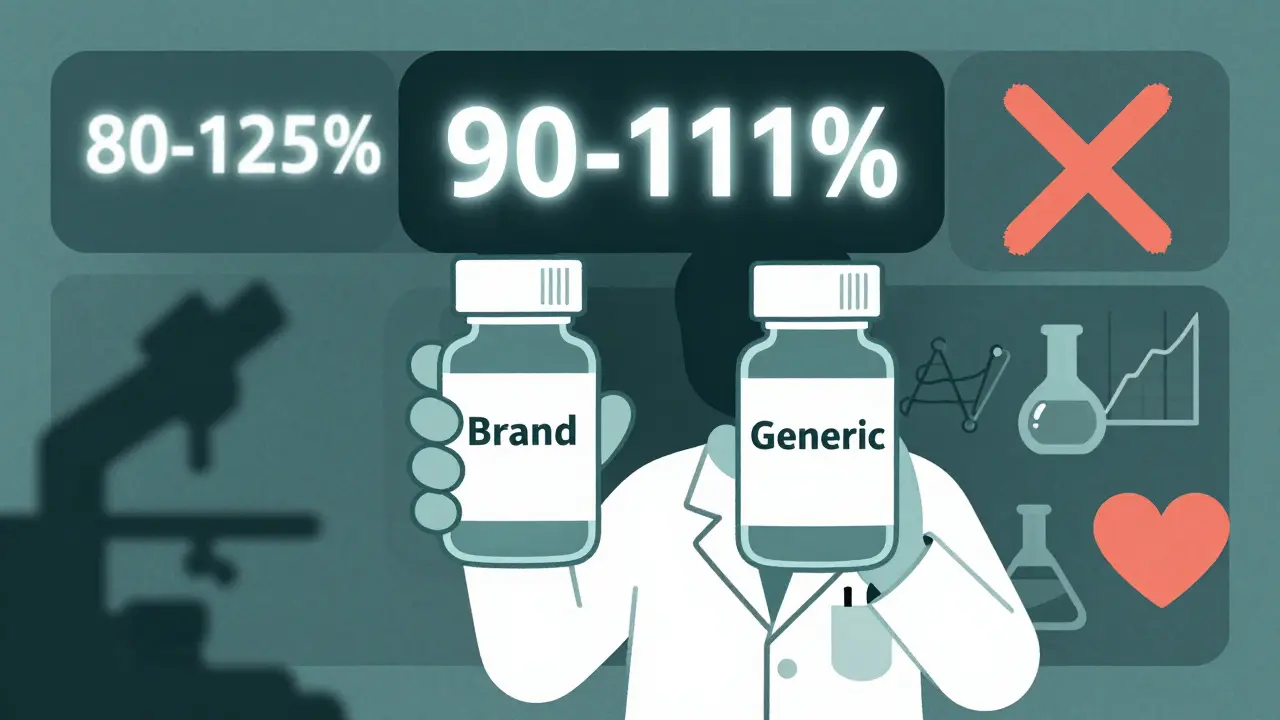

For most generic drugs, the FDA accepts bioequivalence if the average blood concentration of the generic is within 80% to 125% of the brand-name version. That’s a 45% window. For NTI drugs, that’s way too wide. A 20% drop in concentration could mean a seizure. A 20% spike could mean organ damage.

In 2010, the FDA’s Advisory Committee on Pharmaceutical Science and Clinical Pharmacology reviewed the data and voted 11 to 2 that the standard 80-125% range was unsafe for NTI drugs. They recommended tightening it to 90-111%. That’s a 21% window - less than half the size. And it’s not just about the average. The FDA now requires that the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of test to reference drug must fall entirely within 90-111%. No exceptions.

Here’s what that looks like in practice: if a brand-name drug gives an average blood level of 100 ng/mL, a generic must deliver between 90 and 111 ng/mL. A product that delivers 85 ng/mL? Rejected. One that delivers 115 ng/mL? Also rejected. Even if it’s statistically close, it’s not approved.

The Scaled Approach: How the FDA Tests NTI Drugs

The FDA doesn’t just apply a fixed 90-111% rule. It uses something called Reference-Scaled Average Bioequivalence (RSABE). This means the acceptable range can shift slightly based on how variable the original brand-name drug is in the body. If the brand has high within-subject variability (meaning it behaves differently from person to person), the FDA allows a bit more wiggle room - but only if the generic matches that variability exactly.

Here’s how it works: the FDA calculates the within-subject standard deviation (sWR) of the reference drug. If sWR is greater than 0.21, the drug qualifies for scaled limits. But even then, the generic must still pass the traditional 80-125% test. It’s a double barrier. The upper limit of the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of test-to-reference variability must be ≤ 2.5. That’s a technical detail, but it means the generic can’t be more unpredictable than the brand. If the brand is stable, the generic must be just as stable.

These tests require replicate study designs - meaning patients take both the brand and generic versions multiple times, often in different orders. This gives researchers enough data to measure variability accurately. These studies are more expensive, take longer, and need more participants than standard bioequivalence trials. But for NTI drugs, it’s non-negotiable.

Quality Control: More Than Just Blood Levels

It’s not just about how the drug behaves in the body. The FDA also tightens quality control for NTI drugs. For the active ingredient, the acceptable range in the final product is 95-105%, compared to 90-110% for non-NTI drugs. That’s a 10% window versus a 20% window. It sounds small, but in a drug where 1 mg too much can cause toxicity, this matters.

Manufacturers must prove their production process is consistent batch after batch. If one batch of generic tacrolimus has 102% of the labeled amount and the next has 94%, that’s not acceptable. The FDA requires tighter control over raw materials, manufacturing conditions, and final product testing. This isn’t just paperwork - it’s about preventing real-world harm.

Which Drugs Are Classified as NTI?

The FDA doesn’t publish a single public list of NTI drugs. Instead, they’re identified through product-specific guidance documents. If you’re looking for a definitive answer, check the FDA’s website for the guidance on that particular drug. Common NTI drugs include:

- Carbamazepine (antiseizure)

- Phenytoin (antiseizure)

- Warfarin (blood thinner)

- Digoxin (heart medication)

- Valproic acid (mood stabilizer)

- Cyclosporine (immunosuppressant)

- Tacrolimus (immunosuppressant)

- Lithium carbonate (mood stabilizer)

- Everolimus (cancer treatment)

These drugs are used in critical situations - organ transplants, epilepsy, heart failure, psychiatric disorders. A mistake in dosing isn’t just inconvenient; it can be fatal. That’s why even small differences in bioavailability between generics are scrutinized.

Real-World Problems and Controversies

Despite the FDA’s strict standards, doubts remain. Some studies show that two generics approved under NTI rules still aren’t bioequivalent to each other. For example, one generic might be equivalent to the brand, and another might be too, but the two generics differ from each other by more than 10%. This is called “non-transitivity” - and it’s a real problem.

Patients on antiepileptic drugs have reported breakthrough seizures after switching to a generic. Clinicians worry. Pharmacists hesitate. Some states require explicit patient consent before substituting a generic NTI drug. Others ban substitution entirely. The FDA says real-world evidence supports safety, but the anecdotal reports are persistent.

One study found that patients stabilized on brand-name tacrolimus had stable blood levels. When switched to Generic A, levels stayed stable. Switched to Generic B, levels stayed stable. But when switched from Generic A to Generic B? Levels fluctuated - enough to raise concern. This isn’t a flaw in the system; it’s a reminder that bioequivalence doesn’t always equal clinical interchangeability.

How the FDA Responds to Concerns

The FDA acknowledges these concerns. It doesn’t claim the system is perfect. But it stands by its data. Generic NTI drugs approved under these standards are considered therapeutically equivalent to their brand-name counterparts. The agency points to large-scale studies and post-market surveillance showing no increase in adverse events when generics are used.

Still, the FDA is pushing for better education - especially for pharmacists who aren’t used to handling NTI drugs. Many community pharmacists still think “generic = interchangeable” without realizing NTI drugs need special handling. The agency also wants to remove state-level barriers that discourage substitution, arguing that their standards make substitution safe.

What This Means for Patients and Prescribers

If you’re prescribed an NTI drug, you have the right to ask: “Is this the brand, or a generic?” If you’re switched to a generic, monitor for changes. Are you having more side effects? Are your lab numbers off? Talk to your doctor. Don’t assume all generics are the same.

For prescribers: if you’re comfortable with substitution, write “dispense as written” or “no substitution” on the prescription. You’re not being difficult - you’re protecting your patient. The FDA allows substitution, but it doesn’t require it. Your judgment still matters.

For pharmacists: know which drugs are NTI. Check the FDA’s product-specific guidance. Don’t substitute without confirming the generic is approved under NTI standards. If you’re unsure, call the prescriber. It’s better to be cautious than to risk a crisis.

The Global Picture

The U.S. isn’t alone in worrying about NTI drugs. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) and Health Canada have their own rules. But they mostly use a fixed 90-111% limit without scaling. The FDA’s approach is more complex, but also more tailored. It’s not one-size-fits-all - it’s risk-based. That’s why some manufacturers find it harder to get approval in the U.S. than elsewhere.

The FDA admits global harmonization is needed. Right now, a generic approved in Europe might not be approved in the U.S. for the same drug. That creates confusion for patients who travel or for manufacturers trying to enter multiple markets. The agency is working on aligning standards, but progress is slow.

Looking Ahead

About 15% of newly approved generic drugs in 2022 were NTI drugs. That number is rising. More complex medications - especially targeted cancer therapies and immunosuppressants - are falling into the NTI category. The FDA is refining its pharmacometric models to make classification even more accurate. New tools are being developed to predict variability before a drug even hits the market.

But the core message hasn’t changed: for NTI drugs, bioequivalence isn’t a number - it’s a safety promise. The FDA’s standards are strict because the stakes are high. And in medicine, when the margin for error is this small, you don’t cut corners.

What does NTI stand for in drug terms?

NTI stands for Narrow Therapeutic Index. It describes drugs where the difference between an effective dose and a toxic dose is very small. Even minor changes in blood levels can lead to treatment failure or serious side effects. Examples include warfarin, digoxin, and phenytoin.

Why are bioequivalence limits tighter for NTI drugs?

Because small changes in blood concentration can cause harm. For most drugs, a 20% drop or rise is acceptable. For NTI drugs, that same change can trigger seizures, organ toxicity, or dangerous bleeding. The FDA tightened the acceptable range from 80-125% to 90-111% to reduce this risk.

Are all generic NTI drugs safe to substitute?

FDA-approved generic NTI drugs are considered therapeutically equivalent to their brand-name versions. However, some studies show that two approved generics may not be bioequivalent to each other. This is called non-transitivity. Patients should monitor for changes after switching and consult their doctor if symptoms appear.

How does the FDA determine if a drug is NTI?

The FDA uses a pharmacometric approach. A drug is classified as NTI if its therapeutic index is ≤ 3 (toxic dose divided by effective dose). Other factors include the need for therapeutic drug monitoring, small dose adjustments, and low-to-moderate within-subject variability. The agency doesn’t publish a public list - each drug’s status is defined in its product-specific guidance.

Do other countries have the same rules as the FDA for NTI drugs?

No. The EMA and Health Canada use fixed bioequivalence limits (usually 90-111%) without scaling based on variability. The FDA’s approach is more complex - it adjusts limits based on how variable the brand-name drug is in the body. This makes U.S. approval harder but also more tailored to safety.

Lance Nickie

January 14, 2026 at 22:01NTI? More like NTH - No Thanks Here.

Adam Rivera

January 14, 2026 at 23:53Man, I never realized how wild it is that a half-milligram can flip someone from safe to bleeding out. Pharmacies treat all generics like they’re the same, but this? This is why I always ask my doc if it’s brand or generic.

Priyanka Kumari

January 16, 2026 at 07:26This is exactly why I teach my students in India that bioequivalence isn’t just a number-it’s a promise. In countries where generics are the only option, getting this right isn’t optional. The FDA’s standards, while strict, save lives. We need more of this globally.

Rosalee Vanness

January 17, 2026 at 09:12I work in a psych ward, and I’ve seen lithium levels go haywire after a generic switch. One patient went from calm to catatonic in 72 hours. No one told the family it was the med. The pharmacist just swapped it like it was aspirin. This post? It should be mandatory reading for every pharmacy tech. The 90-111% rule? It’s not bureaucracy-it’s a lifeline.

Angel Tiestos lopez

January 17, 2026 at 13:51Bro. I just learned that carbamazepine has a therapeutic index of 2.8. That’s like walking a tightrope over a volcano. 🤯 And they say generics are ‘interchangeable’? Nah. That’s like saying two different brands of airplane fuel are the same because they’re both ‘gasoline.’

Pankaj Singh

January 17, 2026 at 21:33Stop pretending the FDA is perfect. Two generics can both be approved under NTI rules and still kill someone if you switch between them. This is a regulatory farce. The system is broken. You think 90-111% is safe? I’ve seen patients crash because Generic A to Generic B wasn’t ‘transitive.’ The FDA doesn’t care. They just approve and move on.

Milla Masliy

January 18, 2026 at 09:12I’m a pharmacist in rural Ohio, and I’ve had to call doctors 12 times this month because patients were switched to a new generic for warfarin. No one checks the label. No one knows if it’s NTI-approved. The FDA’s rules are good, but they’re useless if the people handing out the pills don’t know them.

Alan Lin

January 18, 2026 at 11:32Let me be blunt: if your generic drug’s bioavailability varies more than 10% from the brand, it shouldn’t be on the shelf. Period. I’ve reviewed dozens of bioequivalence studies for NTI drugs. Half of them are borderline. The FDA’s RSABE model sounds smart, but in practice? It’s a loophole for lazy manufacturers. Real safety means fixed limits, not scaled ones. And stop calling it ‘tailored’-it’s just convenient.

James Castner

January 20, 2026 at 04:37The philosophical underpinning here is staggering. We treat drugs as if they’re mathematical abstractions, when in reality, they’re biological grenades with fuses measured in milligrams. The FDA’s 90-111% threshold isn’t a regulatory choice-it’s an ethical imperative born from decades of corpses. Every time we reduce a life-saving drug to a percentage point, we’re trading humanity for efficiency. And yet, we do it anyway. Why? Because profit margins don’t care if your kidney fails. This isn’t science. It’s a moral test-and we’re failing.

Lethabo Phalafala

January 20, 2026 at 10:11As someone from South Africa where generics are the only option for 90% of patients, I’ve seen what happens when you don’t have these standards. People die quietly. No one reports it. No one cares. The FDA’s rules? They’re not perfect, but they’re the closest thing we have to a safety net. We need this model, not just in the U.S.-but everywhere.

vishnu priyanka

January 21, 2026 at 13:21Bro, imagine being a patient who’s been on brand-name tacrolimus for 5 years. Then you get switched to Generic A-fine. Then Generic B-also fine. But then you switch from A to B? Suddenly your levels go nuts. That’s not a glitch. That’s a betrayal. And the worst part? The pharmacist didn’t even know. They just scanned the barcode and handed it over. This isn’t about science-it’s about trust.

Robin Williams

January 23, 2026 at 08:54NTI drugs are like walking a razor’s edge blindfolded. The FDA’s rules? They’re the only thing keeping us from falling off. I used to think generics were all the same. Then my cousin had a seizure after switching. Turns out, the new generic was ‘approved’ but still threw off his levels. Now I only take brand. Screw the cost. My life isn’t a spreadsheet.

John Tran

January 25, 2026 at 03:38Okay so like… the FDA says NTI means therapeutic index <=3 right? But like… what if the drug’s metabolized differently in different ethnic groups? Like, Asians metabolize phenytoin faster? And the studies are all done on white dudes? So the 90-111% rule… is it even fair? Like… isn’t this just colonial science repackaged as safety? Also, typo: ‘bioavailibility’ in the post lol

mike swinchoski

January 26, 2026 at 21:53People are acting like the FDA is some saint. Newsflash: they approved OxyContin. They approved Vioxx. They’re bureaucrats. They don’t care if you bleed out. They care about paperwork. If you think this system is safe, you’re the problem.