When your doctor can’t get the antibiotics you need, or your hospital runs out of IV bags because the factory in China shut down for a week, you’re not just dealing with a logistics problem-you’re facing the real-world impact of pricing pressure and shortages in healthcare. These aren’t abstract economic terms. They’re what happen when the system that keeps hospitals running starts to break under the weight of global disruptions, labor gaps, and rigid pricing rules. And in 2025, the consequences are still echoing through clinics, pharmacies, and patients’ wallets.

Why Healthcare Can’t Just Print More Medicine

Unlike a T-shirt or a smartphone, you can’t quickly ramp up production of insulin, ventilators, or sterile syringes. These aren’t mass-produced consumer goods. They’re highly regulated, precision-made medical products that require specialized facilities, certified workers, and months of approval before they even hit a shelf. When a supplier in Germany can’t get the raw chemical for a common blood thinner because of a port strike in Rotterdam, or when a U.S. factory loses 30% of its staff to burnout and early retirement, the ripple effect is immediate and deadly. The Cleveland Federal Reserve found that supply shocks in critical sectors raise prices nearly five times more than demand shocks. In healthcare, that math turns into real pain. Between 2021 and 2023, the cost of generic injectables jumped by an average of 22%-some drugs, like epinephrine auto-injectors, saw price hikes over 40% in just two years. Why? Because when supply drops and demand stays flat (or rises, as it does with aging populations), prices don’t just creep up-they spike. And unlike other industries, healthcare often can’t absorb those spikes through competition. There are only a handful of manufacturers for many life-saving drugs. When one fails, there’s no backup.The Labor Shortage That’s Starving Hospitals

It’s not just about missing parts. It’s about missing people. The U.S. labor force participation rate in healthcare support roles-nurses, lab techs, pharmacy assistants-still lagged 2.1 percentage points behind pre-pandemic levels as of mid-2023. That’s not a small gap. It’s the difference between a clinic being able to see 50 patients a day or only 35. When staff are stretched thin, hospitals delay elective procedures, cancel shifts, and turn away patients. And when they can’t hire fast enough, they pay more. Wages for registered nurses rose 14% nationally between 2020 and 2023, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. But here’s the catch: higher wages don’t always fix the problem. In Australia, where I’m based, many rural hospitals still can’t fill positions because of licensing delays and visa backlogs. A nurse trained in the Philippines might be ready to work, but the paperwork takes 11 months. Meanwhile, domestic training programs haven’t scaled up fast enough. The result? Hospitals pay overtime, hire temporary agencies at triple the rate, and pass those costs onto patients through higher fees.When Price Caps Make Things Worse

Governments often try to protect patients by capping prices on essential medicines. It sounds fair. But in practice, it backfires. The Office for Budget Responsibility in the UK found that when energy prices were capped during the 2021 crisis, 27 small providers went bankrupt because they couldn’t cover costs. The same thing happened with generic drugs. In 2022, the U.S. Medicare program froze reimbursement rates for several commonly used antibiotics. Within six months, two major manufacturers stopped producing them. Why? Because the price they were paid didn’t cover the cost of compliance, quality control, or shipping. The drug didn’t disappear because demand dropped. It disappeared because the price was too low to make production viable. Patients were left scrambling. One hospital in Melbourne reported a 68% increase in emergency admissions for untreated infections in Q4 2022 because the standard antibiotic was out of stock. This isn’t theoretical. It’s a pattern. Harvard economist Martin Weitzman showed decades ago that when prices are artificially held down, people don’t just wait-they hoard. Pharmacies saw spikes in bulk purchases of diabetes meds, asthma inhalers, and even antiseptic wipes during the worst of the shortages. That drove local shortages even faster.

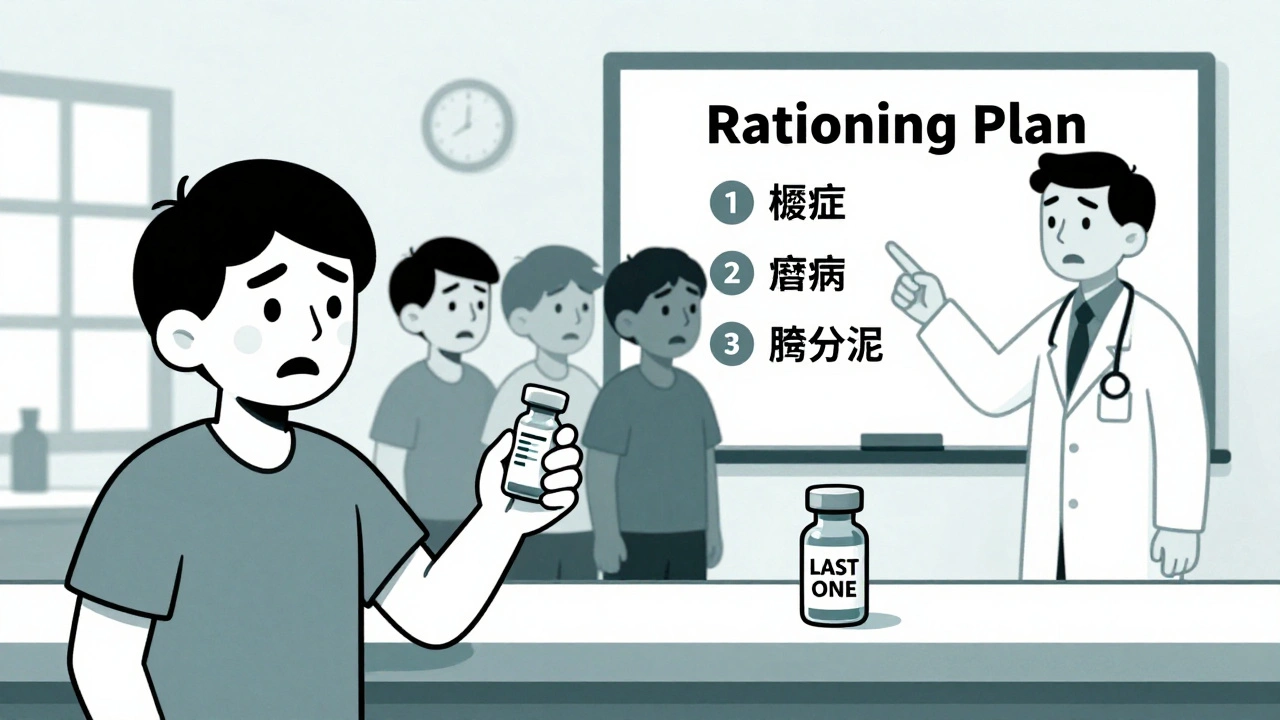

Who Gets Left Behind

The worst effects aren’t felt equally. People with chronic conditions-diabetes, heart disease, kidney failure-are the most vulnerable. They need consistent access to specific drugs. When a batch of insulin is delayed, it’s not a delay. It’s a threat. A 2023 study in the Journal of Health Economics found that patients who missed even one dose of their maintenance medication due to shortages were 37% more likely to be hospitalized within 90 days. Low-income communities and rural areas suffer the most. Urban hospitals can afford to pay premium prices for emergency shipments or switch to more expensive brand-name alternatives. Rural clinics can’t. A 2023 survey of 147 community health centers in Australia found that 83% had to ration at least one essential drug in the past year. Some used expired stock. Others substituted less effective drugs. In one case, a diabetic patient was given a cheaper oral medication instead of insulin-because insulin was unavailable. He was admitted two weeks later with diabetic ketoacidosis.How the System Is Trying to Fix Itself

Some changes are happening. Companies are no longer relying on single-source suppliers. A McKinsey survey of 500 global healthcare firms found that those using dual or triple sourcing reduced supply disruptions by 35%. Hospitals are investing in digital inventory tools that track stock levels in real time and automatically reorder before runs out. One Australian hospital network cut its stockouts by 41% in 18 months just by installing these systems. Governments are also stepping in-with mixed results. Germany relaxed competition rules for pharmaceutical suppliers during peak shortages, allowing competitors to share production data and coordinate distribution. Within six weeks, shortages dropped by 19%. The U.S. passed the Drug Supply Chain Security Act to improve traceability, but implementation has been slow. Meanwhile, the World Health Organization launched a global stockpile of 25 essential medicines in 2024, aimed at emergency distribution during crises. But the real fix isn’t just better logistics. It’s fixing the system that makes healthcare supply chains so fragile. That means investing in domestic manufacturing of critical drugs, speeding up licensing for foreign-trained workers, and letting prices reflect true costs-without letting them spiral out of control.

What Comes Next

The San Francisco Federal Reserve’s Global Supply Chain Pressure Index dropped back to pre-pandemic levels in early 2023. That sounds like good news. But the International Monetary Fund warns that supply chain disruptions will remain 15-20% above normal through 2025-not because of pandemics, but because of climate events, geopolitical splits, and aging infrastructure. Healthcare is especially exposed. As populations age, demand for drugs and devices will grow. But production capacity hasn’t kept up. Only 12% of global pharmaceutical manufacturing capacity is in North America and Europe combined. The rest is concentrated in China and India. One political disruption, one flood, one power outage-and the whole system trembles. The next big threat isn’t another pandemic. It’s complacency. We’ve seen what happens when we treat healthcare supply chains like a background function. They’re not. They’re the nervous system of the entire system. When they fail, people die.What You Can Do

As a patient, you can’t fix global supply chains. But you can be smarter about how you use care:- Ask your doctor if there’s a generic alternative to your prescription-and whether it’s in stock.

- Don’t hoard medications. Taking extra pills “just in case” creates artificial shortages for others.

- Report persistent shortages to your local health department. Data from patients helps trigger policy responses.

- Support policies that fund domestic production of essential medicines and streamline worker visas for healthcare roles.

Why do drug prices go up when there’s a shortage?

When supply drops but demand stays the same or grows, prices rise because manufacturers can charge more-especially if there are few competitors. In healthcare, many drugs have only one or two producers. If one shuts down, the remaining ones raise prices to cover higher production costs, increased shipping, or regulatory expenses. Price controls can make this worse by discouraging production entirely.

Are shortages getting better in 2025?

Some have improved, but not all. Global supply chain pressure has returned to pre-pandemic levels, but healthcare-specific disruptions remain elevated. Shortages of antibiotics, IV fluids, and diabetes supplies are still common in many countries. Climate events, trade barriers, and aging infrastructure mean we’re not back to normal-we’re just in a new kind of instability.

Can governments prevent shortages by stockpiling drugs?

Yes, but only for a limited set of critical items. The WHO’s global medicine stockpile helps during emergencies, but it can’t cover everything. Drugs expire, storage is expensive, and demand is unpredictable. Stockpiling works best for a few high-impact, long-shelf-life medicines like epinephrine or antibiotics-not for hundreds of daily-use drugs.

Why don’t more companies make these drugs locally?

It’s expensive and slow. Building a compliant pharmaceutical plant costs over $500 million and takes 5-7 years. Most companies rely on low-cost manufacturing in Asia because it’s cheaper. Governments are now offering subsidies to bring production home, but progress is slow. Even in Australia, over 80% of active drug ingredients are imported.

How do labor shortages affect drug availability?

Making medicine isn’t automated. It requires skilled technicians, quality control inspectors, and regulatory specialists. When there aren’t enough workers, production slows or stops. In the U.S., over 30% of pharmaceutical plants reported staffing gaps in 2023. In Australia, visa delays for foreign-trained pharmacists meant some hospitals couldn’t fill pharmacy roles for over a year-delaying drug distribution across the whole system.

Elizabeth Crutchfield

December 5, 2025 at 12:35i just got prescribed amoxicillin last week and my pharmacy said they were out… again. i had to drive 45 mins to another town. my dog gets more consistent meds than i do. what the actual f

Gillian Watson

December 6, 2025 at 03:59the fact that we treat lifesaving drugs like commodities instead of public goods is terrifying. we’ve outsourced our survival to a few factories in Asia and now we’re surprised when the supply chain snaps? this isn’t capitalism-it’s negligence dressed up as efficiency

Karl Barrett

December 7, 2025 at 05:14the real issue isn’t just supply chains-it’s the entire economic model of pharmaceuticals. when you have a monopoly on a drug that’s essential for survival, and you know people will pay anything to get it, why would you ever invest in redundancy? the system is designed to fail so profits can soar. it’s not broken. it’s working exactly as intended

Ashley Elliott

December 8, 2025 at 19:57my mom’s on insulin… she’s had to switch brands three times in two years because one batch was ‘unavailable.’ she’s 72. she doesn’t have the energy to fight this. we’re not talking about convenience-we’re talking about people dying because no one wanted to pay for backup systems. please just fix this.

Shofner Lehto

December 9, 2025 at 03:45the labor shortage point is critical. i used to work in hospital logistics. when the pharmacy techs quit because they’re overworked and underpaid, the whole chain collapses. you can have all the inventory software in the world, but if no one’s there to press the reorder button, it’s just a fancy dashboard. we need to treat healthcare workers like humans, not cogs

Rudy Van den Boogaert

December 9, 2025 at 06:35my cousin’s a nurse in rural Nebraska. she told me they’ve been using expired epinephrine auto-injectors because the new ones cost $1200 each and insurance won’t cover them unless the patient’s on Medicare. she cried telling me that. no one should have to choose between following protocol and saving a life

zac grant

December 9, 2025 at 16:35the solution isn’t just stockpiling-it’s domestic manufacturing with smart subsidies. the U.S. spent $200B on defense contractors last year. what if we redirected 10% of that into building FDA-compliant pharma plants in Ohio and Pennsylvania? we could create jobs, reduce dependency, and actually save lives. it’s not rocket science-it’s political will

Augusta Barlow

December 11, 2025 at 00:34you think this is about drugs? no. it’s about the deep state. the FDA, WHO, and Big Pharma are all connected. they want you dependent. they want you scared. that’s why they let shortages happen-it keeps you coming back. they control the supply, they control the price, they control your fear. and now they’re pushing ‘global stockpiles’ to make it look like they’re helping. it’s a trap. you’re being played. wake up

Pavan Kankala

December 12, 2025 at 16:18the system is rigged. the same people who profit from drug shortages are the ones writing the laws. why do you think no one’s held accountable? because accountability is a luxury for the powerless. the rich get brand-name drugs. the poor get expired pills and silence. this isn’t healthcare. it’s a caste system with IV bags

jagdish kumar

December 14, 2025 at 11:56they don’t need to fix it. they just need you to suffer quietly.

Jordan Wall

December 15, 2025 at 07:04the real elephant in the room? regulatory capture. the FDA’s approval process is a 5-year gauntlet that only megacorps can afford. startups? forget it. so you get oligopoly → scarcity → price gouging → public outrage → token reforms. rinse, repeat. it’s not a bug, it’s the feature. also, 🤦♂️

Jenny Rogers

December 16, 2025 at 18:33It is both a moral and economic imperative to restructure the pharmaceutical supply chain with a view toward equitable access and sustainable production. The commodification of human health is not merely an inefficiency-it is an existential failure of civilizational ethics. One must ask: When the mechanism that preserves life becomes the instrument of its denial, what does that say about the society that permits it? The answer, I fear, is not one we wish to confront.