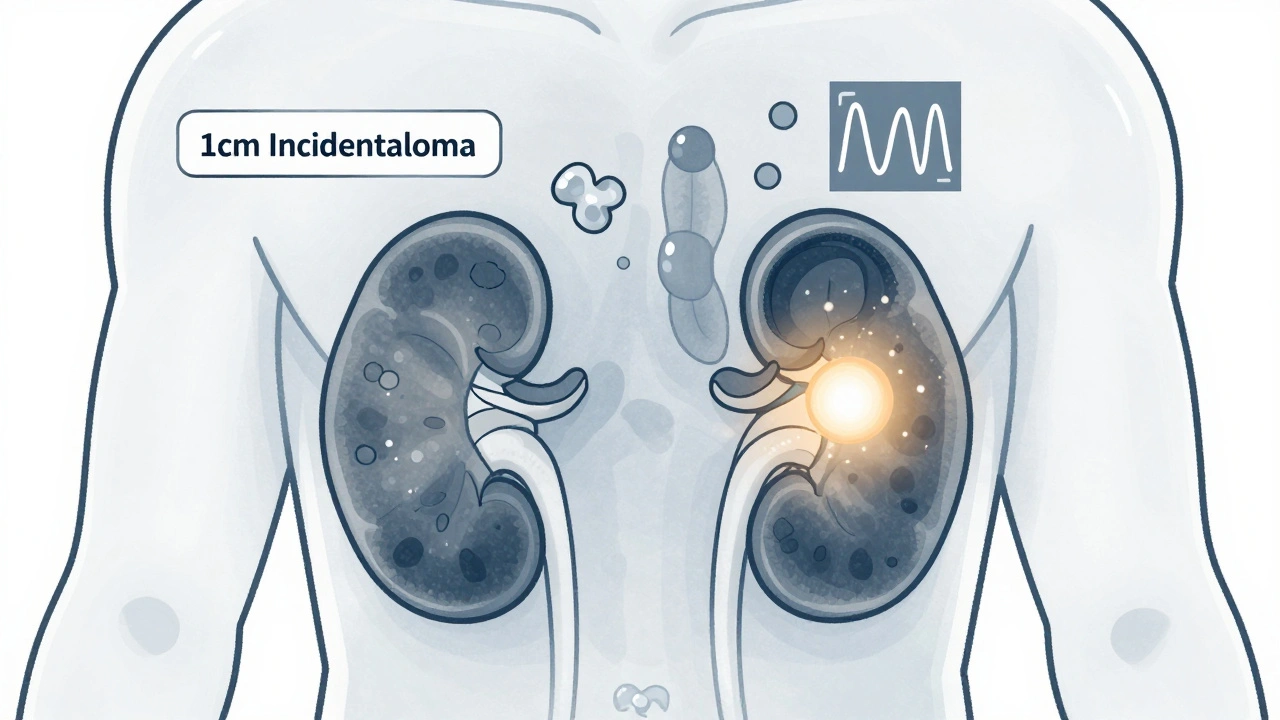

When a CT scan or MRI finds a lump on the adrenal gland - and you weren’t even being checked for anything adrenal-related - it’s called an adrenal incidentaloma. It sounds harmless. Maybe even reassuring. But this seemingly quiet finding can hide something serious. About 1 in 50 people over 50 will have one. By age 70, that number jumps to 1 in 14. Most are harmless. But if you miss the ones that aren’t, the consequences can be life-threatening.

What Exactly Is an Adrenal Incidentaloma?

An adrenal incidentaloma is a mass bigger than 1 cm found by accident during imaging for something else - like a kidney stone, back pain, or even a routine check-up. These masses aren’t symptoms. They’re just dots on a scan. But they’re common. Around 2% of all abdominal scans in adults show one. In people over 70, it’s more than 7%. That’s not rare. It’s routine. The adrenal glands sit right on top of each kidney. They make hormones that control blood pressure, metabolism, stress response, and sex drive. When a tumor forms there, it might not cause any symptoms - but it could be making too much of one of those hormones. Or worse, it could be cancer.Not All Adrenal Tumors Are the Same

There are three main types of adrenal incidentalomas:- Functioning tumors - These make extra hormones. That’s the dangerous kind. They can cause high blood pressure, weight gain, muscle weakness, or even heart problems - even if you feel fine.

- Malignant tumors - These are cancer. Either starting in the adrenal gland (adrenocortical carcinoma) or spreading from elsewhere (like lung or breast cancer).

- Non-functioning benign tumors - These are the most common. About 80% of all incidentalomas. They don’t make hormones. They don’t grow fast. They’re just fatty lumps called adenomas. They don’t need treatment.

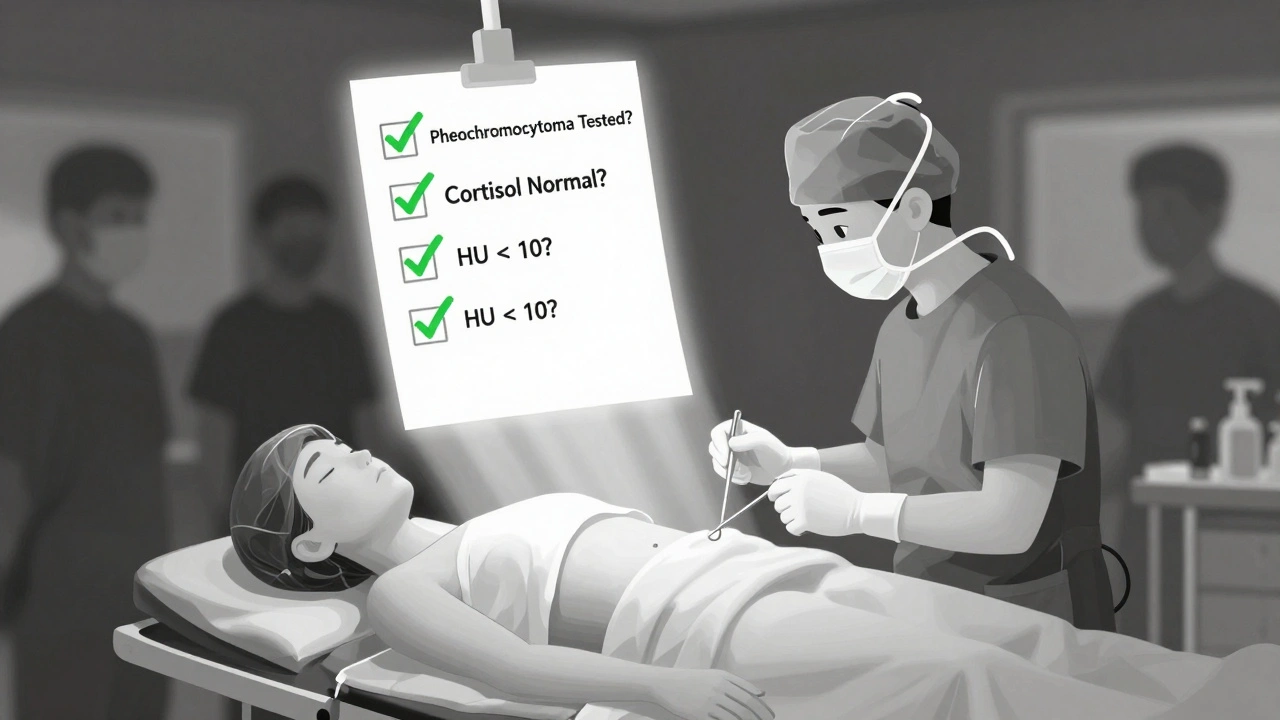

Step 1: Rule Out Pheochromocytoma - The Silent Killer

Every single adrenal incidentaloma must be checked for pheochromocytoma. Why? Because this tumor makes adrenaline and noradrenaline. It’s rare - only about 4% of incidentalomas - but if you don’t catch it before surgery, you could die on the operating table. During anesthesia, the stress of being cut open can trigger a massive adrenaline surge. Blood pressure spikes to dangerous levels. Heart rhythm goes wild. Stroke. Heart attack. Death. The test is simple: a blood test for plasma-free metanephrines or a 24-hour urine test for fractionated metanephrines. If these are high, you need more testing - and you absolutely cannot go to surgery until you’re treated with alpha-blockers for at least two weeks. This isn’t optional. It’s life-saving.Step 2: Check for Cortisol Overproduction - The Silent Metabolic Thief

About 5% of adrenal incidentalomas make too much cortisol. This is called autonomous cortisol secretion. It’s not full-blown Cushing’s syndrome. You might not have a moon face or purple stretch marks. But you still have problems. High cortisol over time raises blood sugar, increases belly fat, weakens bones, and raises your risk of heart disease and stroke. Even if you feel okay, your body is being slowly damaged. The standard test is the 1-mg dexamethasone suppression test. You take a pill at night. The next morning, your cortisol level is checked. If it’s above 1.8 μg/dL (or 50 nmol/L), it’s a red flag. Newer tests - like urinary steroid metabolomics - are now showing even better accuracy, with 92% sensitivity. If cortisol is high, surgery is usually recommended. A 2024 update from the Endocrine Society suggests that if cortisol stays above 5.0 μg/dL after the test, removing the tumor improves blood sugar, blood pressure, and weight - even in people without obvious symptoms.

Step 3: Screen for Aldosterone - The Blood Pressure Saboteur

If you have high blood pressure - especially if you also have low potassium - you need to be checked for aldosterone-producing adenomas. This is primary hyperaldosteronism. It’s found in about 4% of incidentalomas. The test? Blood levels of aldosterone and renin. If aldosterone is high and renin is low, that’s a classic sign. These tumors cause stubborn high blood pressure that doesn’t respond well to normal meds. Removing the tumor often cures it.When Does Size Matter? The 4 cm Rule

Size is a big clue. Tumors under 4 cm are usually benign. Tumors over 4 cm? The risk of cancer jumps.- Under 4 cm: Less than 1% chance of cancer

- 4 to 6 cm: 5-10% chance

- Over 6 cm: Up to 25% chance of adrenocortical carcinoma

What Does the Scan Show? The 10 HU Rule

The first imaging test is usually a non-contrast CT scan. It’s fast, cheap, and tells you a lot. The key number? Hounsfield Units (HU). This measures how dense the tumor is. Fat is less dense. Cancer is more dense. If the tumor has an attenuation value below 10 HU, there’s a 70-80% chance it’s a benign adenoma. That’s a strong green light. No further imaging is needed - unless it’s growing or making hormones. If it’s above 10 HU? You need a contrast-enhanced CT or MRI to see how it behaves with dye. Benign tumors usually lose dye quickly. Cancer holds onto it.Surgery: When and How

You need surgery if:- The tumor is making hormones (pheochromocytoma, cortisol, aldosterone)

- It’s larger than 4 cm

- It has imaging features suggesting cancer

- It’s growing more than 1 cm per year

What About the Benign Ones?

If your tumor is under 4 cm, not making hormones, and looks like a classic adenoma on CT (under 10 HU)? You’re done. No follow-up scans. No blood tests. No stress. Some doctors still order yearly scans out of caution. But the Endocrine Society and AMBOSS agree: that’s unnecessary. You’re just exposing yourself to radiation and anxiety for no reason. Only if the tumor is borderline - say, 10-15 HU, or 3.5 cm - might you get a repeat scan in 6 to 12 months to make sure it’s not growing.Why This Matters - The Real Cost of Missing It

In the U.S., about 4 million adrenal incidentalomas are found every year. That’s a lot of scans, tests, and consultations. The cost? Around $1.2 billion annually. But the real cost isn’t money. It’s the people who get misdiagnosed. The ones who have surgery without pre-op blockade and suffer cardiac arrest. The ones with hidden cortisol excess who develop diabetes or a heart attack years later because no one tested them. Specialized adrenal centers - like those at Columbia, Mayo, or Michigan - have success rates above 90% in patient satisfaction. Community hospitals? Only 63% consistently follow all testing guidelines. That’s a gap. And it’s dangerous.The Future: Better Tests, Smarter Decisions

New tools are coming. Urinary steroid metabolomics can detect cortisol excess with near-perfect accuracy. Genetic testing is starting to identify people at higher risk for adrenocortical cancer. AI is being trained to read adrenal CT scans with fewer errors than human radiologists. The goal isn’t just to find tumors. It’s to find the right ones - and leave the rest alone.What You Should Do If You Have One

If you’ve been told you have an adrenal incidentaloma:- Don’t panic. Most are harmless.

- Ask for a referral to an endocrinologist who specializes in adrenal disorders.

- Make sure you get tested for pheochromocytoma - no exceptions.

- Ask about the 1-mg dexamethasone test for cortisol.

- Request your CT scan’s Hounsfield unit value. Under 10? Good sign.

- If the tumor is over 4 cm or growing, ask about surgical evaluation.

- Don’t accept yearly scans unless your case is truly unclear.

Are adrenal incidentalomas always cancerous?

No. About 80% of adrenal incidentalomas are benign, non-functioning adenomas that don’t cause symptoms or require treatment. Only about 2-8% turn out to be malignant, and most of those are metastases from other cancers, not primary adrenal cancer.

Can an adrenal incidentaloma cause high blood pressure?

Yes. If the tumor produces excess aldosterone or adrenaline (pheochromocytoma), it can cause resistant high blood pressure. Even cortisol overproduction can lead to hypertension over time. That’s why hormone testing is essential for every incidentaloma.

Do I need surgery if my tumor is small and not producing hormones?

No. If your tumor is under 4 cm, has a CT value under 10 Hounsfield units, and shows no signs of hormone overproduction, no treatment is needed. Follow-up scans are not recommended unless the mass grows or changes appearance.

What happens if I don’t get tested for pheochromocytoma before surgery?

You risk a life-threatening hypertensive crisis during anesthesia. Pheochromocytomas release large amounts of adrenaline when stressed. Without pre-op blockade, surgery can trigger a stroke, heart attack, or sudden death. Testing is mandatory before any adrenal procedure.

How long does it take to recover from adrenal surgery?

Most patients recover in 2 to 4 weeks after laparoscopic surgery. Recovery is faster than open surgery. If you had a cortisol-secreting tumor, you may need steroid replacement for weeks or months until your other adrenal gland adjusts. Always follow up with your endocrinologist.

Can adrenal incidentalomas come back after removal?

If the tumor was a benign adenoma, it won’t come back. If it was cancer, there’s a risk of recurrence, especially if it was large or invasive. Follow-up scans and hormone tests are needed for at least 5 years after cancer removal. For benign, non-functioning tumors, recurrence is extremely rare.

Why do some doctors recommend yearly scans for small tumors?

Some doctors do it out of caution, but current guidelines from the Endocrine Society say it’s unnecessary for small, benign-looking tumors. Repeated CT scans expose you to radiation and cause anxiety without improving outcomes. Only monitor if the tumor is borderline in size or appearance.

Is there a blood test that can confirm if an adrenal tumor is cancerous?

No single blood test can confirm cancer. Diagnosis relies on imaging features (size, texture, growth rate) and hormone levels. In rare cases, a biopsy may be considered, but it’s risky and often inconclusive. Surgery and pathology are still the gold standard for confirming malignancy.

Billy Schimmel

December 6, 2025 at 10:18So basically if you get a random scan for back pain and they find a dot on your adrenal, you’re now in a medical maze that costs a grand and gives you anxiety? Cool. I’ll just ignore it until I pass out on the operating table.

Max Manoles

December 6, 2025 at 15:40The 10 HU rule is one of the most underappreciated tools in diagnostic radiology. A tumor under 10 Hounsfield units has an 80% likelihood of being a benign adenoma - a fact that should eliminate unnecessary follow-ups in over 70% of cases. Yet, many institutions still default to annual CTs out of defensive medicine. This is not evidence-based care; it’s liability-driven noise.

Katie O'Connell

December 6, 2025 at 17:48It is imperative to underscore that the Endocrine Society’s 2024 guidelines represent a paradigmatic shift in the management of adrenal incidentalomas. The evidentiary basis for abandoning routine surveillance of non-functioning, sub-4 cm lesions with attenuation values under 10 HU is robust, and the continued practice of repeat imaging constitutes a form of iatrogenic harm, both financially and psychologically.

Chris Park

December 8, 2025 at 16:06They say 'most are harmless' - but who’s really behind this? Big Pharma? The imaging industry? They want you scared so you get more scans, more biopsies, more surgery. Pheochromocytoma is rare - they’re blowing it up to sell you drugs. And why do they never mention that cortisol tests can be skewed by stress? You’re being manipulated.

Nigel ntini

December 9, 2025 at 00:38This is one of those posts that makes you feel like you’ve just been handed a survival guide for a system that’s trying to scare you into submission. If you’ve got an incidentaloma, don’t panic - but do ask for the HU value, push for the metanephrines test, and find an endo who actually knows what they’re talking about. You’ve got this.

pallavi khushwani

December 10, 2025 at 07:17i used to think medical stuff was all black and white, but this? it’s like a whole universe of gray. like, if my tumor’s 3.8 cm and 9 hu, am i just... fine? or should i be sweating? it’s wild how much we’re expected to just trust the numbers and not the fear.

Dan Cole

December 11, 2025 at 19:03Let me cut through the fluff: if your tumor is over 4 cm, you’re not ‘maybe’ getting surgery - you’re getting it. The 25% cancer risk isn’t a suggestion. It’s a countdown. And if your doctor says ‘let’s wait and see’ without ordering steroid metabolomics or checking your metanephrines? That’s malpractice wrapped in patience. You’re not being cautious - you’re being reckless.

Clare Fox

December 12, 2025 at 17:31i got my ct report and it said 8 hu. i called my doc and she said ‘oh good, no worries.’ i asked if i should get a second opinion and she laughed. i felt like an idiot. but then i read this and realized maybe i’m not. maybe i just needed someone to say: it’s okay to ask.

Akash Takyar

December 13, 2025 at 11:41It is imperative that patients, upon receiving a diagnosis of adrenal incidentaloma, exercise due diligence by requesting the specific Hounsfield unit measurement, the results of plasma-free metanephrines, and the outcome of the 1-mg dexamethasone suppression test. Failure to do so may result in the omission of life-threatening pathologies. Vigilance is not paranoia - it is responsibility.

Arjun Deva

December 13, 2025 at 18:49They say 'don't panic'... but what if they're lying? What if the 'benign' tumors are just hiding? What if the '10 HU rule' was made up by a radiologist who hated his job? And why does no one ever talk about how many people die because they got the wrong test? I think this whole system is rigged.