When a hospital decides to switch from a brand-name drug to a generic, it’s not just about saving money. It’s a complex decision shaped by clinical safety, supply reliability, staff workload, and hidden financial deals that most patients never see. Behind every drug on a hospital shelf is a committee of pharmacists, doctors, and administrators weighing evidence, rebates, and real-world risks. This is hospital formulary economics - and it’s where the real cost control happens.

What Is a Hospital Formulary, Really?

A hospital formulary isn’t just a list of approved drugs. It’s a living system managed by a Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) committee that meets monthly or quarterly to decide what gets stocked, what gets kicked out, and why. Unlike retail pharmacies, where patients pick from a wide range of options, hospitals use closed or partially closed formularies. That means only drugs pre-approved by the committee are available - unless there’s an emergency or special exception.

The goal? To make sure every medication used is safe, effective, and affordable. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) says this isn’t a purchasing decision - it’s clinical governance. The P&T committee doesn’t just look at price tags. They dig into bioequivalence studies, nursing workflow, storage needs, and even how easy a pill is to swallow. A drug might be cheap, but if it causes more errors or requires extra monitoring, it’s not worth it.

How Generics Make It Onto the Formulary

Not all generics are created equal. The FDA says a generic must be therapeutically equivalent to its brand-name counterpart. But in a hospital setting, that’s just the starting point. P&T committees demand more. They want proof that the generic performs the same in real patients - especially in critical care.

For simple pills like metformin or lisinopril, that’s usually straightforward. But for complex generics - like inhalers, injectables, or topical creams - the story changes. The FDA’s 2022 report found only 62% of complex generic applications got approved on the first try, compared to 88% for standard ones. Why? Because delivery matters. A generic asthma inhaler might have the same active ingredient, but if the particle size or spray pattern is slightly off, it won’t reach the lungs the same way. That can mean worse outcomes, more ER visits, and higher long-term costs.

Committees also look at the manufacturer’s track record. A generic made by a company with frequent shortages or quality issues won’t make the cut, even if it’s the cheapest option. One hospital pharmacist in a 2023 survey said they rejected a low-cost generic IV antibiotic because the manufacturer had three recalls in two years. The risk wasn’t worth the savings.

The Tiered System: Cost Isn’t Always What It Seems

Hospitals use tiered formularies to guide prescribing. Tier 1 is for preferred generics - the cheapest, most reliable options. Tier 2 includes non-preferred generics and some brand-name drugs. Tiers 3 and above are for expensive or specialty drugs, often requiring prior authorization.

But here’s the catch: the lowest list price doesn’t mean the lowest net cost. Many generic manufacturers offer rebates, discounts, or service agreements that aren’t visible on the invoice. Dr. Emily Chen from Massachusetts General Hospital pointed out in a 2023 interview that some generics with higher list prices end up costing less after rebates. That’s why committees now demand full financial disclosures before approving any drug. A drug that looks like a bargain on paper might be a financial trap.

And then there’s the 340B Drug Pricing Program. Hospitals that serve low-income patients can buy generics at deeply discounted rates through this federal program. That changes the math entirely. A drug that’s too expensive for a regular hospital might be the obvious choice for a 340B-covered facility - even if it’s not the cheapest on the open market.

Why Switching Generics Can Backfire

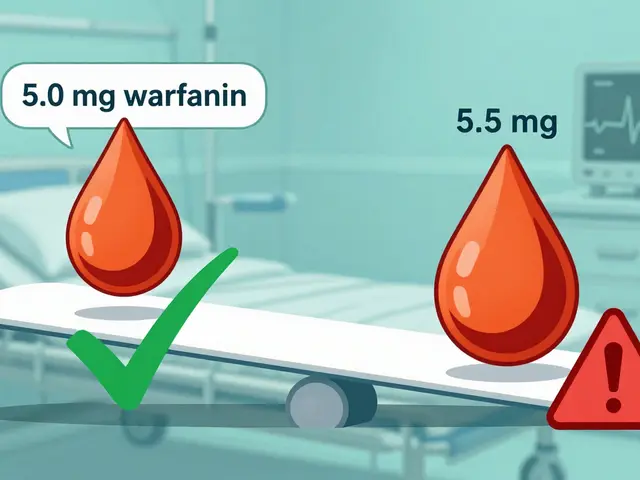

Switching from brand to generic sounds simple. But in practice, it’s risky. A case at Johns Hopkins Hospital showed that switching to a generic anticoagulant led to unexpected spikes in lab monitoring. Nurses had to check blood levels more often, which increased staffing needs and delayed patient discharges. The cost savings on the drug were wiped out by extra labor.

That’s why successful programs don’t just swap drugs - they build protocols. Mayo Clinic cut cardiovascular drug costs by $1.2 million a year after implementing a structured transition plan. They didn’t just change the label. They trained staff, updated EHR alerts, monitored outcomes for six months, and adjusted dosing based on patient response. The key? They didn’t assume bioequivalence meant clinical equivalence.

Surveys show 68% of hospital pharmacists struggle with therapeutic equivalence for complex generics. Inhalers, injectables, and IV solutions are especially tricky. Even tiny differences in how the drug is delivered can affect how well it works. One pharmacist described a generic epinephrine auto-injector that had a slower activation time - enough to matter in anaphylaxis.

Supply Chains and Shortages: The Hidden Crisis

One of the biggest threats to formulary stability is drug shortages. In November 2023, the FDA recorded 298 active shortages of generic drugs - the highest number since tracking began in 2011. Many of these are older, low-margin generics made by just one or two manufacturers.

When a generic runs out, hospitals are forced to buy non-formulary alternatives - often at three to five times the price. A 2023 survey found 84% of hospital pharmacists faced at least one critical shortage in the last quarter. That’s not just a logistics problem - it’s a financial one. Formularies now include backup options for high-risk drugs, even if they’re more expensive. It’s insurance against chaos.

Market concentration makes this worse. The top five generic manufacturers now control 58% of the hospital market. If one of them has a production issue, dozens of drugs vanish overnight. That’s why some hospitals are moving toward multi-source sourcing - keeping two or three approved generics for the same drug, even if one is slightly more expensive.

Technology Gaps and Human Errors

Even with the best policies, mistakes happen. Only 37% of hospitals have automated alerts in their electronic health records that block non-formulary prescriptions. That means doctors can still order a drug that’s not approved - and often don’t realize it.

A study at the University of Michigan found 15-20% of prescriptions ignored formulary rules. Why? Lack of training, time pressure, or simply not knowing the rules. New P&T committee members take 6-9 months to become proficient. They need to understand bioequivalence studies, rebate structures, and how to read an AMCP dossier - a detailed clinical and economic submission required by 92% of academic hospitals.

Some hospitals are starting to integrate pharmacogenomics into their decisions. If a patient has a genetic variant that affects how they metabolize a drug, that can influence which generic is safest. Twenty-eight percent of academic centers now consider genetic data when evaluating narrow therapeutic index drugs like warfarin or clopidogrel. It’s still rare, but it’s growing.

The Future: Transparency, Complexity, and Value-Based Contracts

The 2023 Consolidated Appropriations Act will require full transparency in generic pricing by January 2025. That means hospitals will finally see what rebates and discounts are really being offered - not just the list price. Experts predict this will force manufacturers to compete on quality and reliability, not just hidden deals.

The FDA’s GDUFA III program is investing $4.3 million to speed up approval of complex generics. That could help fill gaps in injectables and inhalers by 2026. But until then, hospitals are stuck playing a high-stakes game: balancing cost, safety, and supply.

More institutions are moving toward value-based contracts. Instead of paying a fixed price per pill, they tie payment to outcomes. If a generic leads to fewer readmissions or complications, the manufacturer gets a bonus. Forty-seven percent of academic medical centers are now using this model for high-cost generics. It’s a shift from buying drugs to buying results.

What Works - And What Doesn’t

Successful formularies share three things: clinical leadership, data-driven decisions, and flexibility. The best P&T committees are led by pharmacists - at least half of the members must be clinical pharmacists, according to AMCP guidelines. They use real-world data, not just trial results. And they don’t lock themselves into one supplier.

What fails? When formularies are driven by rebate size alone. The ASHP warned in 2021 that rebate-driven decisions risk patient safety. A drug with a big discount might save money today but cause harm tomorrow. And when hospitals ignore supply chain risks, they pay the price later - in higher costs and worse outcomes.

Bottom line: Hospital formulary economics isn’t about picking the cheapest drug. It’s about picking the right drug - the one that works, stays in stock, and doesn’t overload the staff. Generics are essential to controlling costs. But their value isn’t in the price tag. It’s in the science, the systems, and the people who make sure they’re used safely.

Why do hospitals use closed formularies instead of open ones?

Hospitals use closed formularies to control costs, reduce errors, and ensure consistent care. Unlike retail pharmacies that encourage patient choice, hospitals prioritize safety and efficiency. A closed formulary limits options to drugs that have been clinically vetted and are reliably available. This reduces prescribing variation, prevents drug interactions, and makes it easier to train staff and monitor outcomes. About 78% of academic medical centers use closed models, compared to just 42% of commercial health plans.

Are all generic drugs the same as brand-name drugs?

By FDA standards, generics must have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand. They must also be bioequivalent - meaning they work the same way in the body. But in hospitals, especially for complex drugs like inhalers or injectables, small differences in inactive ingredients or delivery systems can affect how well the drug works. That’s why P&T committees don’t rely solely on FDA approval - they look at real-world performance and clinical data before adding a generic to the formulary.

How do rebates affect generic drug selection in hospitals?

Rebates can make a drug with a higher list price cheaper than one with a lower price. Manufacturers offer rebates to pharmacies or health systems in exchange for preferred formulary placement. But these deals are often hidden in contracts. Hospitals now require full financial disclosures before approving a generic. The 2025 transparency rules will force these rebates into the open, making it harder to choose drugs based on kickbacks instead of clinical value.

What role do pharmacists play in formulary decisions?

Pharmacists are the backbone of the P&T committee. At least half of the members must be clinical pharmacists, according to AMCP guidelines. They review clinical studies, interpret bioequivalence data, assess supply risks, and analyze cost-effectiveness. They also train staff, monitor outcomes, and troubleshoot problems when a generic doesn’t work as expected. Without their expertise, formularies would be driven by price alone - not patient safety.

Why are generic drug shortages so common in hospitals?

Most generic drugs are made by a small number of manufacturers, often overseas. When one factory has a quality issue or shuts down, the entire supply chain breaks. These drugs are low-margin, so companies don’t invest in backup production. In 2023, there were 298 active shortages - the highest ever. Hospitals respond by stockpiling, finding alternatives, or paying premium prices - all of which strain budgets and compromise care.

Reema Al-Zaheri

November 19, 2025 at 21:04Formulary decisions are far more complex than most assume-bioequivalence doesn't guarantee clinical equivalence, especially with injectables and inhalers. The FDA’s approval is a baseline, not a guarantee. I’ve seen generic epinephrine auto-injectors with delayed activation times; in anaphylaxis, milliseconds matter. Hospitals must demand real-world data, not just regulatory checkboxes.

Michael Salmon

November 21, 2025 at 16:27Stop pretending this is about patient safety. It’s all about rebates and kickbacks disguised as clinical governance. P&T committees are just corporate gatekeepers with white coats. If you’re not getting a 40% rebate, you’re not even on the table. The ‘clinical leadership’ narrative is a cover for greed.

Timothy Reed

November 22, 2025 at 02:40While some of the concerns raised are valid, it’s important to recognize the systemic pressures hospitals face. The P&T committee model, though imperfect, represents a structured, evidence-based approach to managing limited resources. Many institutions have successfully reduced costs without compromising outcomes-through data, training, and multi-source sourcing. This isn’t perfect, but it’s better than the alternative.

Angela Gutschwager

November 23, 2025 at 06:14So… generics are risky? Shocking. 🙄

Andy Feltus

November 23, 2025 at 09:16Let me get this straight-we’re spending millions on committees to decide which $0.02 pill to buy, while ignoring that 80% of drug spending comes from 20% of high-cost agents? The real formulary crisis isn’t metformin-it’s the $50,000 oncology drugs no one dares question. This whole thread is like debating whether to use paper towels or hand dryers while the building’s on fire.

seamus moginie

November 25, 2025 at 06:44Man, the FDA’s approval process is a joke. I’ve worked in three Irish hospitals, and we’ve had generics that worked like charm, others that made patients sick. The system’s broken. They need to stop trusting these Chinese factories. We’re paying for safety, not just a price tag.

Zac Gray

November 26, 2025 at 09:46It’s fascinating how the article frames this as a clinical decision-making problem, when in reality, it’s a supply chain and market concentration issue. The fact that five manufacturers control 58% of the hospital generic market is a systemic vulnerability. And yet, we keep acting like this is just about pharmacists choosing between two pills. It’s not. It’s about monopolistic control, offshore manufacturing, and the collapse of domestic production. We’ve outsourced our drug security-and now we’re surprised when things break. The solution isn’t more committees. It’s antitrust enforcement and domestic production incentives.

Steve and Charlie Maidment

November 27, 2025 at 04:36I don’t know why everyone’s so surprised. The whole system is rigged. You’ve got pharmacists who don’t even know how to read an AMCP dossier, and you’ve got manufacturers who know exactly how to game the rebate system. And then you’ve got doctors who just click the first thing that pops up in the EHR because they’re rushed. Nobody’s accountable. And now we’re pretending that adding another layer of paperwork-like value-based contracts-is going to fix it? Please. It’s just a new way to make the same mistakes with more buzzwords.

Paige Lund

November 27, 2025 at 11:12Wow. So we’re paying for a whole team of people to decide if a pill is ‘good enough’? And you call this ‘clinical governance’? I’d rather just let doctors pick what they want and let patients pay the difference.

Joe Durham

November 28, 2025 at 02:43It’s easy to criticize the system from the outside, but the people working in P&T committees are often the most overworked, underappreciated professionals in the hospital. They’re the ones reading through 200-page AMCP dossiers at midnight because the next meeting’s in 48 hours. They’re not bureaucrats-they’re the last line of defense between patients and dangerous, unreliable meds. Let’s not forget that.

Derron Vanderpoel

November 28, 2025 at 13:48Okay so I just read this whole thing and I’m crying? No, wait-I’m not crying, I’m just furious. Imagine being a nurse and having to monitor a patient’s blood levels every two hours because the generic they switched to doesn’t work right? And then your manager says, ‘But it’s cheaper!’? That’s not savings. That’s cruelty. We’re not saving money-we’re trading safety for spreadsheets. Someone needs to wake up.

Christopher K

November 29, 2025 at 19:20Why are we letting foreign manufacturers dictate our hospital formularies? This is national security. If China shuts down a factory, we’re left with no epinephrine? No antibiotics? We need to bring generic production back to America-NOW. No more rebates, no more loopholes. Just American-made, American-tested, American-approved drugs. Period.

harenee hanapi

November 30, 2025 at 17:21So let me get this straight-you’re telling me that after all this, the real answer is… more committees? More paperwork? More meetings? And you wonder why people hate healthcare? I’ve been in this system for 17 years. We’re not fixing anything. We’re just making the same mistakes with more PowerPoint slides. The only thing that matters is whether the patient gets better. Not the rebate. Not the FDA approval. Not the tier. Just whether they wake up tomorrow. And right now? We’re failing.