Why cleanroom standards matter more than ever for generic drugs

Generic drugs make up over 90% of prescriptions filled in the U.S., but they’re not just cheaper copies. They must be identical in safety, strength, and effectiveness to the brand-name version. That’s not easy to guarantee when you’re producing millions of pills, injections, or inhalers in a factory. The difference between a safe drug and a dangerous one often comes down to one thing: the air around it.

Every time someone breathes, talks, or moves in a manufacturing room, they release tiny particles - skin flakes, hair, microbes. In a regular room, that’s fine. In a cleanroom for generic drug production, it’s a disaster waiting to happen. Contamination can cause infections, reduce potency, or trigger allergic reactions. The FDA doesn’t just inspect the final product - it inspects the entire environment where it’s made. And if the air isn’t clean enough, the entire batch gets rejected.

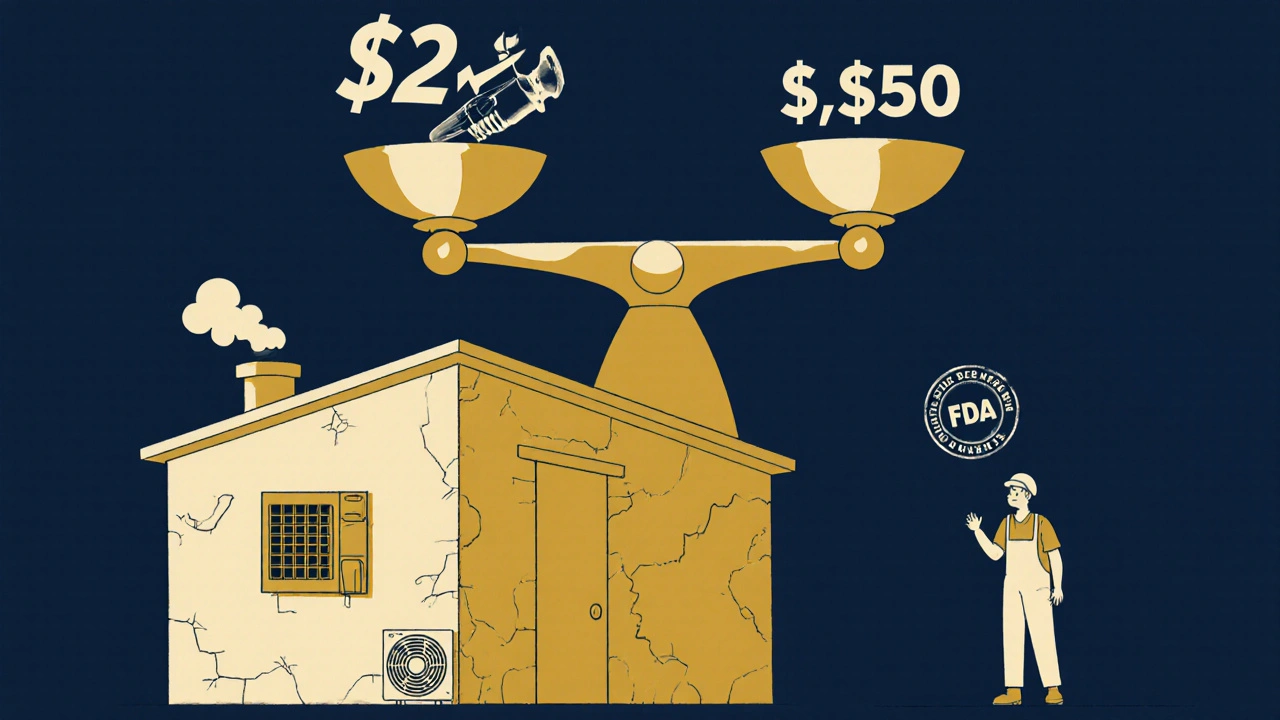

That’s why cleanroom standards aren’t optional. They’re the backbone of generic drug quality. Without them, bioequivalence is just a claim. With them, patients can trust that their $5 generic pill works just like the $100 brand-name version.

How cleanroom grades work: From ISO Class 5 to Grade D

Cleanrooms aren’t all the same. They’re divided into four levels - Grade A, B, C, and D - each with strict rules about how many particles can float in the air. These levels are based on the ISO 14644-1 standard, which counts particles as small as 0.5 micrometers. That’s 1/100th the width of a human hair.

Grade A is the cleanest. It’s used for filling sterile injectables, like insulin or chemotherapy drugs. At this level, no more than 3,520 particles per cubic meter are allowed during operation. That’s like having just 3 or 4 dust specks in a room the size of a small closet. Air flows in one direction, like a silent waterfall, pushing contaminants out. The room stays under positive pressure so dirty air from outside can’t sneak in.

Grade B is the background environment for Grade A. It’s less strict but still tightly controlled. Think of it as the antechamber where workers prepare before entering the ultra-clean zone. It allows up to 3.5 million particles per cubic meter during operations - still far cleaner than a hospital operating room.

Grade C is for making tablets and capsules that aren’t sterile. Here, particle limits jump to 35 million per cubic meter. It’s still far cleaner than a typical office, but it doesn’t need laminar airflow. Grade D is the lowest level, used for packaging or final labeling. It only has limits at rest - meaning when no one’s working. Once people start moving around, the rules loosen up.

These aren’t just numbers on a chart. They’re the line between a drug that saves lives and one that could harm them.

Regulatory differences: FDA vs. EU vs. ICH

Not all countries play by the same rules - even when they say they do.

The FDA doesn’t directly use ISO numbers in its regulations. Instead, it says facilities must be designed to prevent contamination. But in practice, inspectors expect you to meet ISO Class 5 for sterile products. The European Union, however, spells it out clearly in Annex 1 of its GMP rules. If you’re exporting to Europe, you must hit those exact particle counts and airflow rates.

ICH guidelines help bridge the gap. They’re international agreements that make it easier for companies to sell drugs in the U.S., EU, and Japan. But even with ICH, differences remain. Japan requires monitoring at 1.0-micron particle size - something the U.S. and EU don’t mandate. And while the FDA allows Grade C for non-sterile solids, some experts argue that’s too lenient. A 2020 study showed identical drug performance from Grade D and Grade C facilities. So why pay more for stricter controls?

The answer? Risk. The FDA doesn’t just care about what’s in the bottle - it cares about how you got there. If your process is inconsistent, your product might be fine today but fail tomorrow. That’s why inspectors now focus on your contamination control strategy - not just your particle counts.

The real cost of cleanrooms: Money, time, and human error

Building a Grade A cleanroom costs between $250 and $500 per square foot. For a 5,000-square-foot facility, that’s over $1 million just to build the space. Then comes the HVAC system - the lungs of the cleanroom. It needs to swap the air 60 to 90 times per hour. That’s not just expensive to install. It’s expensive to run. Electricity bills for these systems can hit $100,000 a year.

But the biggest cost isn’t hardware - it’s people.

Workers must wear full gowns, masks, gloves, and boot covers. Training for proper gowning takes 40 to 60 hours. One wrong move - touching your face, moving too fast, skipping a step - can send particle counts soaring. A 2022 survey found that 42% of cleanroom deviations came from human error. That’s why many companies now use video monitoring and AI-powered alerts to catch mistakes in real time.

Small generic manufacturers feel this the hardest. A company making a $0.50 heparin syringe can’t afford the $2.3 million upgrade to meet Grade B standards. One FDA inspection found marginal particle excursions - not enough to harm patients, but enough to trigger a warning letter. For a small player, that’s the end of the road.

Success stories and failures: What happens when cleanrooms work - or don’t

When cleanrooms work right, the results are powerful. Teva’s generic version of Copaxone - a multiple sclerosis drug - was rejected twice because of contamination. After installing advanced isolator systems in their Grade A zone, contamination dropped from 12 events per year to just 2. They got FDA approval on the third try. That’s millions in saved revenue and thousands of patients getting affordable treatment.

But when they fail, the consequences are brutal. In 2022, Aurobindo Pharma had to recall $137 million worth of sterile injectables because their Grade B cleanroom didn’t monitor airborne microbes properly. The FDA issued a consent decree - meaning the company had to stop production until it fixed everything. That’s not just a fine. It’s a shutdown.

The worst case? The 2012 New England Compounding Center outbreak. Contaminated steroid injections caused a fungal meningitis epidemic. Over 750 people got sick. 64 died. The cleanroom was a mess - no proper airflow, no monitoring, no training. It wasn’t a generic drug manufacturer, but the lesson was the same: dirty air kills.

What’s changing in 2025 and beyond

Standards aren’t staying still. The EU’s revised Annex 1, which took effect in August 2023, now requires continuous air monitoring - not just spot checks. That means sensors running 24/7, sending alerts if particle levels spike. The FDA says it’s coming around to this too.

Robots are starting to replace humans in the cleanest zones. Automated arms fill vials. AI systems track gowning compliance. By 2028, McKinsey predicts automation will cut cleanroom operating costs by 25-30%. That’s huge for generic makers who’ve been squeezed by thin margins.

And the demand for complex generics is rising. Biosimilars, inhalers, and injectables with complex delivery systems need even tighter controls. The FDA expects half of all new generic applications by 2025 to need Grade A or B environments - up from 35% in 2022.

Meanwhile, emerging markets like India are spending an average of $4.2 million per facility to upgrade. That’s $1.4 million more than U.S. facilities. Why? Older buildings, weaker infrastructure, and less access to modern HVAC tech.

How to get it right: Practical steps for manufacturers

If you’re building or upgrading a cleanroom, here’s what you need to do:

- Start with your product. Sterile injectables? You need Grade A. Oral tablets? Grade C might be enough.

- Design for airflow, not just space. Laminar flow is non-negotiable for Grade A. Don’t skimp on the HVAC.

- Train your people like surgeons. Gowning isn’t a formality - it’s a life-or-death skill. Retrain every six months.

- Install continuous monitoring. Spot checks are outdated. Real-time data catches problems before they become recalls.

- Document everything. SOPs for cleaning, monitoring, gowning, and maintenance aren’t paperwork - they’re your legal shield.

- Use free resources. The FDA offers free cGMP training. ISPE and PDA have guides that walk you through every step.

Don’t wait for an inspection to find out you’re behind. The best time to upgrade was five years ago. The second-best time is now.

Final thought: Cleanrooms aren’t a cost - they’re a commitment

Generic drugs exist because patients need affordable medicine. But affordability shouldn’t mean lower quality. Cleanroom standards are how we keep that promise. They’re not about perfection. They’re about control. About knowing, every single day, that the drug someone is taking won’t hurt them.

For the small manufacturer, it’s hard. For the regulator, it’s necessary. For the patient, it’s everything.

Deirdre Wilson

November 26, 2025 at 06:34So basically, if you sneeze near a pill machine, the FDA might shut you down? 🤯 I love how we turn medicine into a sci-fi movie where dust is the villain.

Bethany Buckley

November 28, 2025 at 01:35The epistemological weight of cleanroom governance cannot be overstated. We are not merely manufacturing pharmaceuticals-we are engineering ontological certainty in an entropic world. ISO Class 5 is not a standard; it is a sacrament of epistemic integrity. 🌌✨

Ryan C

November 29, 2025 at 18:56LOL you guys are missing the point. The FDA doesn’t even use ISO classifications-they just pretend to. Annex 1 is the real bible. And FYI, Japan monitors 1.0-micron particles because they’re paranoid about rice dust. 🍚🔍

Gina Banh

November 30, 2025 at 17:04I’ve been in cleanrooms where the air feels like a silent glacier. You don’t breathe-you *respect* the air. And yeah, human error is the #1 killer. I once saw a guy adjust his mask with a gloved hand… and the alarm screamed. No one laughed after that.

Amanda Meyer

December 2, 2025 at 11:02This is a critical conversation. The cost of compliance is not a burden-it’s a moral contract with patients. When we cut corners on air quality, we’re not saving money. We’re gambling with lives. The 2012 outbreak wasn’t an accident. It was negligence dressed as economics.

Damon Stangherlin

December 2, 2025 at 11:29I work in a small generic plant and this article hit home. We’re using Grade C for oral solids and honestly? It’s fine. We monitor like crazy, train weekly, and use AI alerts. Maybe the FDA should focus on actual risk-not just particle counts. 💪

Cynthia Boen

December 3, 2025 at 14:07So we’re spending millions so some guy in a bunny suit can walk slowly? Meanwhile, people can’t afford insulin. This system is broken.

Mqondisi Gumede

December 4, 2025 at 11:26USA and EU think they own cleanrooms? In South Africa we make pills in garages and they work better than your overpriced $500k machines. Your standards are colonial. We don’t need your ISO to save lives

Stephanie Deschenes

December 4, 2025 at 18:16The real win here is continuous monitoring. Spot checks are like checking your car’s oil once a year. If your particle sensor spikes at 3 AM and you don’t know until morning-you’re already late.

Jesús Vásquez pino

December 6, 2025 at 04:51I’m not saying we shouldn’t have cleanrooms. But why are we still using 1970s gowning protocols? Why not AI-powered motion tracking and auto-gowning robots? We’re treating pharmaceuticals like a monastery when we could be treating them like a SpaceX launchpad.

Dan Rua

December 7, 2025 at 13:44This is so well written. I’m a quality lead at a mid-sized plant and we just upgraded to continuous monitoring last year. The drop in deviations? 68%. Also, the training videos we made with our staff? Got 200k views on LinkedIn. People care about this stuff.

hannah mitchell

December 8, 2025 at 17:45I read this at 2am after a 12-hour shift. Honestly? It made me feel proud. We don’t get thanked. But this? This is why we show up.

vikas kumar

December 9, 2025 at 11:45In India, we’re building new facilities with EU-grade specs because we want to export. But the real challenge? Power outages. No electricity = no airflow. So we’ve started solar-backed HEPA systems. It’s messy, but it works. We’re learning as we go.

Ginger Henderson

December 10, 2025 at 22:04So… if I make a generic version of Advil in my garage with a shop vac and a face mask, is that illegal? Just asking for a friend.