When you make a change to how a medicine is made-whether it’s swapping out a machine, moving a step to a different room, or tweaking the recipe-even small tweaks can trigger serious regulatory consequences. In pharmaceutical manufacturing, manufacturing changes aren’t just operational updates. They’re legal events. And if you get the notification or approval wrong, you could face a warning letter, a product recall, or even a shutdown.

Why Manufacturing Changes Are Heavily Regulated

Pharmaceutical products aren’t like sneakers or smartphones. You can’t just update the design and ship it. Every pill, injection, or inhaler must be identical in safety, strength, and effectiveness from batch to batch, year after year. That’s why regulators like the FDA, EMA, and Health Canada treat manufacturing changes as potential threats to patient safety.A change in the equipment used to mix an active ingredient, even if it’s a newer model from the same vendor, could alter how particles bond. A shift in humidity control during drying might affect how fast a tablet dissolves. These aren’t hypotheticals. In 2023, the FDA issued four warning letters specifically for misclassified equipment changes. One company replaced a lyophilizer (freeze-dryer) without approval-and ended up distributing a batch with inconsistent potency.

The system exists because patients depend on consistency. If a generic blood pressure drug suddenly becomes less effective because of an unapproved change, people could have strokes. That’s why regulators demand proof-before you make the change-that quality hasn’t been compromised.

The Three-Tier System: What You Must Do When You Change Something

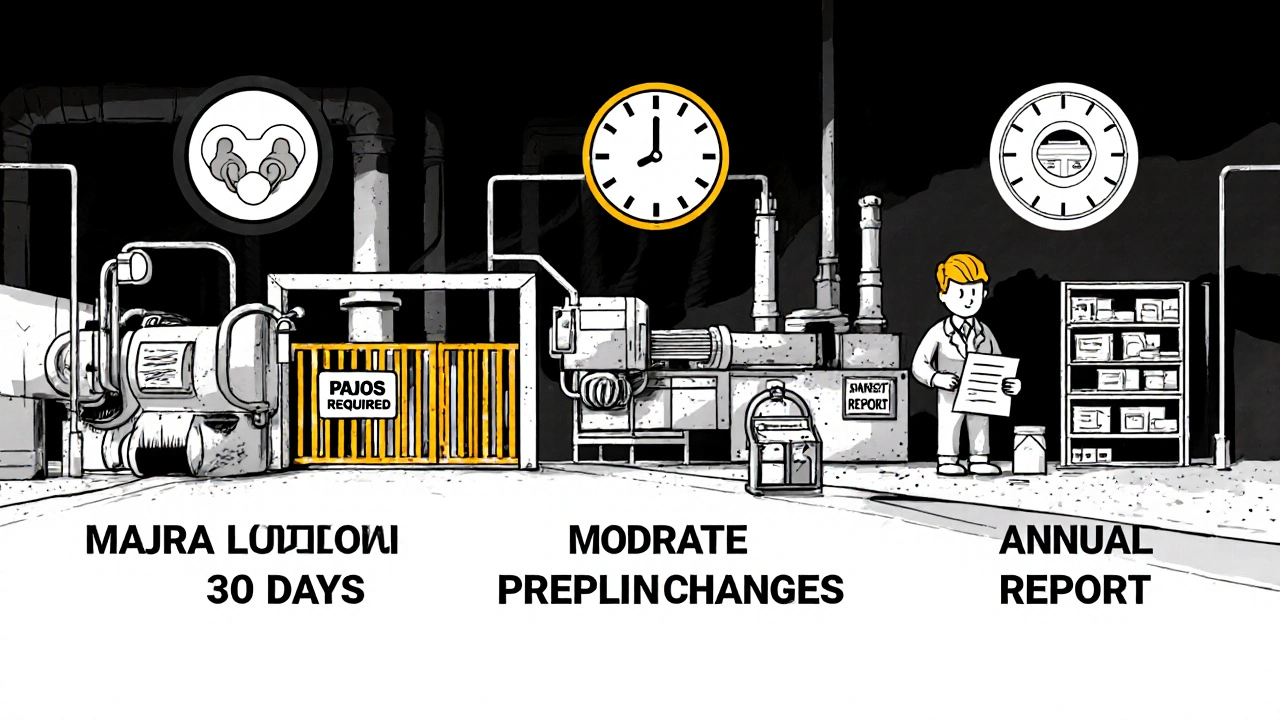

In the U.S., the FDA uses a clear, three-category system under 21 CFR 314.70. It’s not optional. You must classify every change correctly.- Major changes require a Prior Approval Supplement (PAS). You can’t even start making the change until the FDA says yes. This applies to things like switching the chemical synthesis route for the active ingredient, moving production to a new country, or changing a critical piece of equipment that affects how the drug behaves. If you’re unsure, assume it’s major.

- Moderate changes use a Changes Being Effected in 30 Days (CBE-30). You can make the change, but you must notify the FDA at least 30 days before distributing the new version. Examples: replacing a mixer with an identical model from the same manufacturer, or changing the labeling on a container. If the equipment is truly equivalent-same principle, same materials, same dimensions-it’s usually CBE-30.

- Minor changes go in your annual report. These are low-risk tweaks like moving a non-critical step within the same facility, updating a software patch on a non-critical machine, or changing a supplier for a non-critical excipient. You don’t need to notify the FDA ahead of time, but you must document it and report it within 60 days of your application’s anniversary date.

Get this wrong, and you’re in violation. In 2019, Apotex was hit with a warning letter for classifying a major change as moderate. The FDA found that a change in the tablet compression process altered the drug’s dissolution rate-potentially affecting how well it worked. That’s not a paperwork error. That’s a safety risk.

How Other Regions Handle It

The U.S. isn’t the only player. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) uses a different system: Type IA, IB, and II.- Type IA (minor): You can implement immediately and notify within 12 months. Think: changing a printer for labels or updating a document number.

- Type IB (moderate): You must get approval before implementing. This includes replacing a filling machine or changing a cleaning procedure. Unlike the FDA’s CBE-30, you can’t start until approved.

- Type II (major): Full review required before any change. This covers new manufacturing sites or major process overhauls-similar to FDA’s PAS.

Health Canada uses Level I (prior approval), Level II (notify and wait), and Level III (annual report). The structure is similar to the FDA’s, but the timelines and documentation expectations vary.

The key difference? The FDA lets you implement moderate changes immediately, as long as you notify within 30 days. The EMA doesn’t. If you’re a global manufacturer, you can’t use one system for all markets. You need a change control plan that adapts to each region’s rules.

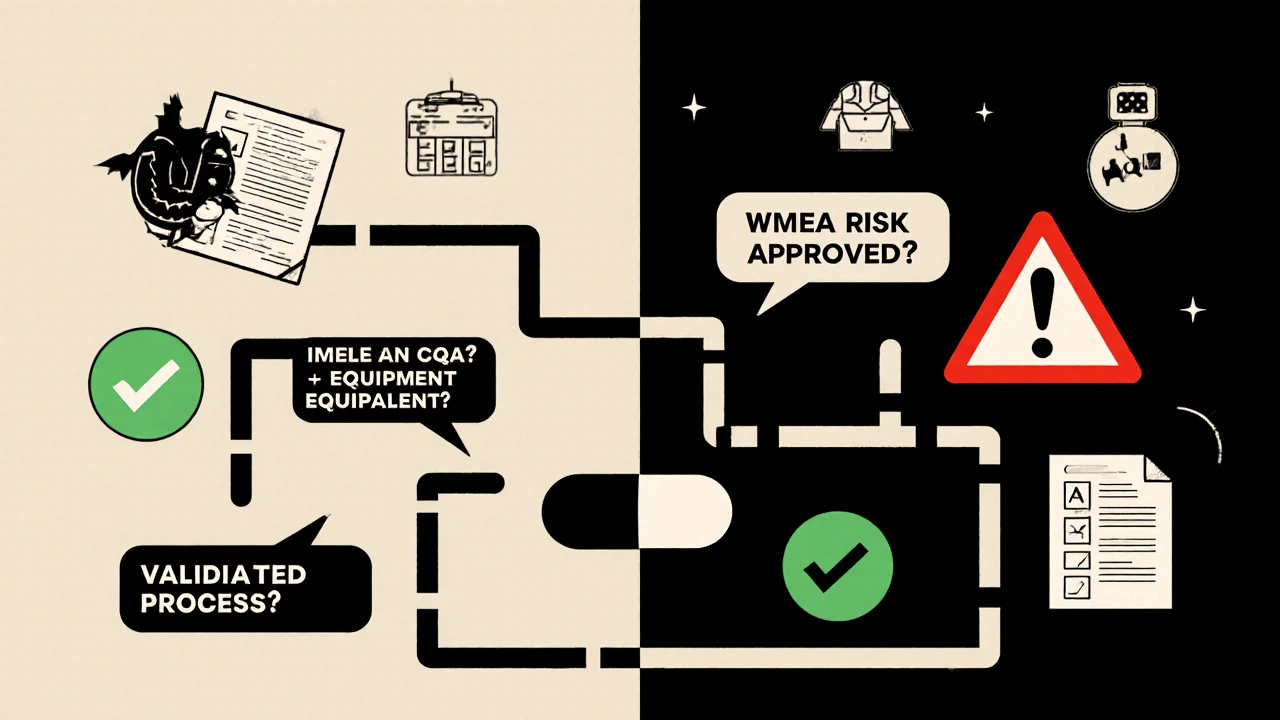

What Makes a Change Major vs. Minor?

It’s not always obvious. A new tablet press might seem like a simple swap. But if that press changes how the powder is compressed, it could alter the drug’s release profile. That’s a major change.Here’s what regulators look at:

- Impact on Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs): Does the change affect how the drug dissolves, how stable it is, or how pure it is?

- Impact on Critical Process Parameters (CPPs): Does it change temperature, pressure, mixing time, or flow rates that were validated during initial approval?

- Equipment equivalence: Is the new machine the same in design, material, and operation? FDA says: same principle, same dimensions, same materials. If you’re unsure, treat it as major.

- Process validation status: If the process isn’t fully validated, any change is likely major.

Companies like Pfizer use internal risk-scoring tools with 15+ factors to classify changes. They look at historical performance, validation data, and even operator training records. If you’re a smaller company without that infrastructure, start with the FDA’s 2021 guidance on biologics-it includes a table of common changes and their recommended categories.

Documentation You Can’t Skip

No matter the category, you must document everything. Regulators don’t care about your verbal explanation. They want paper-or digital-proof.For every change, you need:

- A formal change request form with justification

- A risk assessment (FMEA is the industry standard)

- Comparability study data: at least three consecutive batches made before and after the change, tested for identity, strength, purity, and potency

- Updated process validation reports

- Facility diagrams showing where the change occurred

- Sign-offs from QA, manufacturing, and regulatory affairs

One mid-sized generic manufacturer spent 37 hours debating whether a tablet press replacement was CBE-30 or PAS. Why? Because the API’s particle size specification was ambiguous. That’s not inefficiency-that’s the cost of uncertainty.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Here are the top three errors companies make:- Assuming “equivalent” means “identical”. Just because the new machine has the same brand and model number doesn’t mean it’s equivalent. If the internal seals are a different material, or the motor speed is calibrated differently, it’s not equivalent.

- Delaying notification. Waiting until after production starts to file a CBE-30 is a violation. The FDA expects submission 30 days before distribution-not after you’ve already shipped product.

- Ignoring comparability studies. If you don’t prove the new version performs the same as the old one, you have no basis for classification. Statistical analysis of batch data isn’t optional-it’s required.

And don’t think small companies are safe. In 2022, 22% of FDA warning letters were related to manufacturing changes-and 37% of those involved equipment. Small firms are just as likely to get caught.

What’s Changing in 2025?

The system is evolving. The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance on quality risk management (based on ICH Q9) is pushing companies to use data-driven risk assessments instead of rigid checklists. Some companies are already using real-time monitoring sensors to prove process stability after a change-reducing the need for lengthy batch testing.The EMA introduced accelerated pathways for certain Type IB changes in 2023, cutting review times from 60 to 30 days. And with more companies moving to continuous manufacturing (where every step is connected), even small equipment tweaks now often require PAS submissions.

By 2025, experts predict 40% of new change submissions will include real-time quality data. That’s the future: less paperwork, more proof.

How to Get It Right Every Time

If you’re responsible for managing manufacturing changes:- Start with the FDA’s 2021 final guidance on biologics-even if you don’t make biologics, the examples are gold.

- Build a cross-functional team: QA, manufacturing, validation, and regulatory affairs must review every change together.

- Use FMEA for risk scoring. Don’t guess.

- When in doubt, ask the FDA. Their 2021 guidance says: “Early consultation is encouraged.” You can request a pre-submission meeting. It costs time, but it saves you from a warning letter.

- Train your team. ASQ data shows regulatory specialists need 18 months of hands-on experience to classify changes consistently.

Manufacturing changes aren’t about speed. They’re about safety. The goal isn’t to get through the process-it’s to ensure that every pill that leaves your facility is exactly what the patient expects.

What happens if I make a manufacturing change without approval?

If you implement a major or moderate change without proper notification or approval, you’re in violation of FDA regulations. Consequences can include warning letters, product recalls, import alerts, or even a federal order to stop distribution. In 2023, four companies received warning letters specifically for unapproved equipment changes. The FDA treats this as a serious quality failure, not a paperwork error.

Can I use the same change classification for the U.S. and Europe?

No. The FDA’s PAS/CBE-30/annual report system doesn’t map directly to the EMA’s Type IA/IB/II. For example, a CBE-30 in the U.S. (where you can implement immediately after notice) is closer to a Type IB in Europe (where you must wait for approval). Global manufacturers need separate change control procedures for each region. Using one system across markets creates compliance risk.

How do I know if new equipment is “equivalent”?

The FDA defines “equivalent” as having the same principle of operation, same critical dimensions, and same material of construction. For example, replacing a tablet press with another model from the same manufacturer using identical tooling and compression force settings qualifies. But if the new machine uses a different type of feeder or has a different drying system, it’s not equivalent-even if it’s newer or faster. Document every difference and test for impact on critical quality attributes.

Do I need to run new stability studies for every change?

Not always, but you must prove comparability. For moderate changes, you typically need data from three consecutive batches made after the change, tested against historical data for key quality attributes like dissolution, potency, and impurity levels. Statistical analysis is required. For major changes, full stability studies (6-12 months) are often needed. The key is showing no meaningful difference in product performance.

How long does it take to get FDA approval for a major change?

A Prior Approval Supplement (PAS) typically takes 6-12 months for review, depending on complexity and whether the FDA requests additional data. For biologics or complex changes, it can take longer. You cannot ship product made with the new process until the FDA approves your supplement. Planning ahead is critical-don’t wait until you’re ready to make the change to start the submission.

Linda Rosie

November 23, 2025 at 14:58Just read this through twice. The part about equipment equivalence is spot on. I’ve seen teams assume ‘same model’ means ‘same outcome’-and then the FDA shows up with a warning letter. Always test the CQAs. Always.

Demi-Louise Brown

November 25, 2025 at 06:43Clarity like this is rare. Thank you for laying out the tiers so plainly. This should be mandatory reading for every QA trainee.

Matthew Mahar

November 26, 2025 at 16:22OH MY GOD. I just spent 4 hours arguing with my boss about a mixer change and now I realize we classified it as CBE-30 when it was PAS. I think I’m gonna cry. Or quit. Or both. 😭

John Mackaill

November 27, 2025 at 05:54The EMA vs FDA difference trips up so many global teams. I’ve seen companies get burned trying to use a single change log. You need regional playbooks. Period.

Adrian Rios

November 28, 2025 at 19:52Let me tell you about the time we replaced a lyophilizer because the old one was ‘ancient’ and ‘sounded like a jet engine.’ We thought, ‘It’s just a new machine, same specs.’ Turns out the new one had a different condenser coil geometry. Changed the sublimation rate. Batch 3 had 12% potency drop. We had to recall 18,000 vials. QA team cried. Regulatory team panicked. The CEO called it ‘a $2M lesson in humility.’ I still wake up in sweat thinking about it. Don’t assume. Validate. Document. Repeat.

Casper van Hoof

November 29, 2025 at 20:02The regulatory framework, while ostensibly designed for safety, functions as a structural barrier to innovation. One wonders whether the cost of compliance-both in time and capital-ultimately serves the patient, or merely the bureaucracy. The system rewards caution over progress, and in doing so, may delay life-saving improvements under the guise of consistency.

Richard Wöhrl

December 1, 2025 at 15:45Just a quick note: For comparability studies, make sure you’re using statistical process control (SPC) charts-not just averages. The FDA loves to see control limits, CpK values, and trend analysis. Also, don’t forget to include impurity profiles in your comparability package. I’ve seen people focus only on potency and miss a new degradant that showed up in LC-MS. It’s not just ‘did it work?’-it’s ‘is it the same, down to the last molecule?’

Pramod Kumar

December 3, 2025 at 08:59Bro, this is like the Bible for pharma folks. I work in a small lab in Bangalore, and we don’t have a fancy FMEA team. But I printed this out, laminated it, and taped it to our wall. Now every time someone says, ‘It’s just a small change,’ I point to the table. They shut up. 😎

Brandy Walley

December 4, 2025 at 02:39So you’re telling me I can’t just upgrade my tablet press because it’s 2025 and the old one is from 2008? What a joke. People die from bad meds? Yeah, and people die from waiting 12 months for FDA paperwork. This system is broken.

shreyas yashas

December 4, 2025 at 04:34Man, I used to think this stuff was boring. Then I saw a colleague get fired over a misclassified change. Now I read every line. It’s not about rules-it’s about not letting someone down because you skipped a step.

Suresh Ramaiyan

December 4, 2025 at 19:39There’s a quiet wisdom here: safety isn’t the absence of change-it’s the presence of intention. Every change, no matter how small, carries a ripple. The system asks us to slow down, not because it’s slow, but because the stakes are human. We’re not just making pills. We’re making trust.

Katy Bell

December 5, 2025 at 14:55That part about real-time sensors replacing batch testing? I’m all in. My team’s testing 30+ batches per change. We’re drowning in data. If we can prove stability with sensors and AI, why are we still doing manual HPLC runs from 1998?

Ragini Sharma

December 7, 2025 at 05:23so like… if i just change the font on the label… is that a type ia? 😅